Part 3, following on from part 1 and part 2.

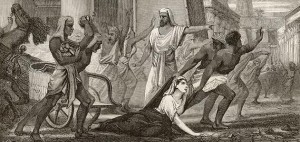

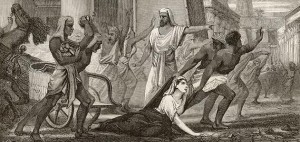

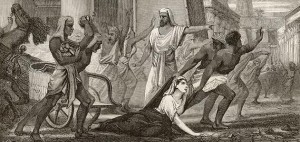

Chapter XV.—Of Hypatia the Female Philosopher.

Chapter XV.—Of Hypatia the Female Philosopher.

There was a woman at Alexandria named Hypatia, daughter of the philosopher1 Theon, who made such attainments in literature and science, as to far surpass all the philosophers of her own time. Having succeeded to the school of Plato and Plotinus, she explained the principles of philosophy to her auditors, many of whom came from a distance to receive her instructions. On account of the self-possession and ease of manner, which she had acquired in consequence of the cultivation of her mind, she not unfrequently appeared in public in presence of the magistrates. Neither did she feel abashed in coming to an assembly of men. For all men on account of her extraordinary dignity and virtue admired her the more. Yet even she fell a victim to the political jealousy which at that time prevailed. For as she had frequent interviews with Orestes, it was calumniously reported among the Christian populace, that it was she who prevented Orestes from being reconciled to the bishop. Some of them therefore, hurried away by a fierce and bigoted zeal, whose ringleader was a reader named Peter, waylaid her returning home, and dragging her from her carriage, they took her to the church called Cæsareum, where they completely stripped her, and then murdered her with tiles2.After tearing her body in pieces, they took her mangled limbs to a place called Cinaron, and there burnt them. This affair brought not the least opprobrium, not only upon Cyril,but also upon the whole Alexandrian church. And surely nothing can be farther from the spirit of Christianity than the allowance of massacres, fights, and transactions of that sort. This happened in the month of March during Lent, in the fourth year of Cyril’s episcopate, under the tenth consulate of Honorius, and the sixth of Theodosius.3

1 and mathematician. He arranged Euclid’s Elements and Ptolemy’s Handy Tables.

2 Tile shards, presumably, i.e. flayed her alive with something like this.

3 Socrates and Sozomenus, Ecclesiastical Histories, ed. and trans. Philip Schaff, WM. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Michigan, p. 160

Part 2 of series of events, which began here.

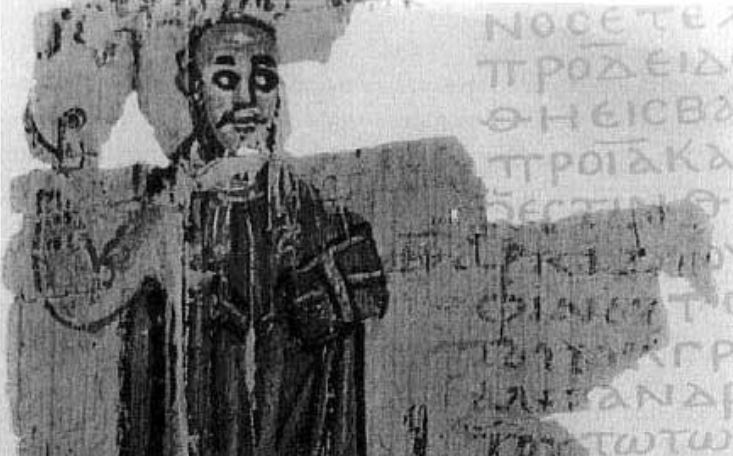

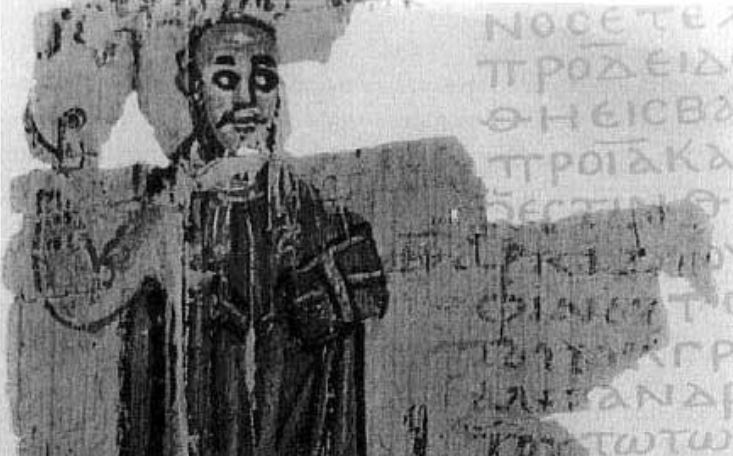

Theophilus Bishop of Alexandria with the Serapeum he destroyed

1 The previous Bishop of Alexandria, who caused the Serapeum, along with other pagan temples, to be destroyed.

2 Socrates and Sozomenus, Ecclesiastical Histories, ed. and trans. Philip Schaff, WM. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Michigan, p. 160

The head of a statue of Aphrodite with some Christian improvements

Libanius (ca. 314 – ca. 394 C.E.) was a Greek-speaking teacher of rhetoric of the Sophist school. Libanius was a friend of the emperor Julian II (later called The Apostate), with whom some correspondence survives, and in whose memory he wrote a series of orations; they were composed between 362 and 365. Libanius remained a pagan, though this did not stop him cultivating long-lasting friendships with Christians, both as private individuals and as imperial officials. In 386 he wrote an oration addressed to the Emperor Theodosius I, ‘complaining about gangs of monks who wandered the Syrian countryside demolishing pagan shrines and terrorizing peasants.’1 Addressing such an oration to Theodosius was a delicate, not to say dangerous thing to do, but poor Libanius, despite all evidence to the contrary, seemed to have still have harboured some hope for religious toleration if not actual freedom. In 391 Theodosius forbade on pain of prescription of property, torture and even death, the practising of any religion other than Christianity, or even visiting the temples, which he closed down, giving some of the buildings over to various bishoprics. In 386 however, he had not yet gone so far. Sacrificing was forbidden, but praying or worshipping with incense was not.

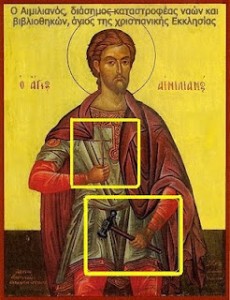

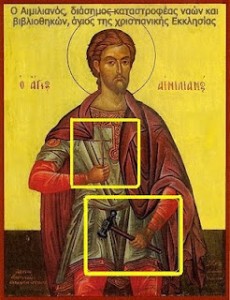

Saint Aemilianus holding the hammer he used on statues and temples

I shall, indeed, appear to many to undertake a matter full of danger in pleading with you for the temples, that they may suffer no injury, as they now do. But they who have such apprehensions seem to me to be very ignorant of your true character. For I esteem it the part of an angry and severe disposition, for any one to resent the proposal of counsel which he does not approve of: but the part of a mild and gentle and equitable disposition, such as yours2 is, barely to reject counsel not approved of. For when it is in the power of him to whom the address is made to embrace any counsel or not, it is not reasonable to refuse a hearing which can do no harm; nor yet to resent and punish the proposal of counsel, if it appear contrary to his own judgement; when the only thing that induced the adviser to mention it, was a persuasion of its usefulness.

…

After his death3 in Persia, the liberty of sacrificing remained for some tim e: but at the instigation of some innovators, sacrifices were forbidden by the two brothers4, but not incense;—-which state of things your law has ratified. So that we have not more reason to be uneasy for what is denied us, than to be thankful for what is allowed. You, therefore, have not ordered the temples to be shut up, nor forbidden any to frequent them: nor have you driven from the temples or the altars, fire or frankincense, or other honours of incense. But those black-garbed people5, who eat more than elephants, and demand a large quantity of liquor from the people who send them drink for their chantings, but who hide their luxury by their pale artificial countenances,—-these men, O Emperor, even whilst your law is in force, run to the temples, bringing with them wood, and stones, and iron, and when they have not these, hands and feet. Then follows a Mysian prey6, the roofs are uncovered, walls are pulled down, images are carried off, and altars are overturned: the priests all the while must be silent upon pain of death. When they have destroyed one temple they run to another, and a third, and trophies are erected upon trophies: which are all contrary to [your] law. This is the practice in cities, but especially in the countries. And there are many enemies every where. After innumerable mischiefs have been perpetrated, the scattered multitude unites and comes together, and they require of each other an account of what they have done; and he is ashamed who cannot tell of some great injury which he has been guilty of. They, therefore, spread themselves over the country like torrents, wasting the countries together with the temples: for wherever they demolish the temple of a country, at the same time the country itself is blinded, declines, and dies.

e: but at the instigation of some innovators, sacrifices were forbidden by the two brothers4, but not incense;—-which state of things your law has ratified. So that we have not more reason to be uneasy for what is denied us, than to be thankful for what is allowed. You, therefore, have not ordered the temples to be shut up, nor forbidden any to frequent them: nor have you driven from the temples or the altars, fire or frankincense, or other honours of incense. But those black-garbed people5, who eat more than elephants, and demand a large quantity of liquor from the people who send them drink for their chantings, but who hide their luxury by their pale artificial countenances,—-these men, O Emperor, even whilst your law is in force, run to the temples, bringing with them wood, and stones, and iron, and when they have not these, hands and feet. Then follows a Mysian prey6, the roofs are uncovered, walls are pulled down, images are carried off, and altars are overturned: the priests all the while must be silent upon pain of death. When they have destroyed one temple they run to another, and a third, and trophies are erected upon trophies: which are all contrary to [your] law. This is the practice in cities, but especially in the countries. And there are many enemies every where. After innumerable mischiefs have been perpetrated, the scattered multitude unites and comes together, and they require of each other an account of what they have done; and he is ashamed who cannot tell of some great injury which he has been guilty of. They, therefore, spread themselves over the country like torrents, wasting the countries together with the temples: for wherever they demolish the temple of a country, at the same time the country itself is blinded, declines, and dies.

…

This is saint Nicholas. Yes, the same one that supposedly brings Christmas presents.

This being the state of things, the husbandman is impoverished, and the revenue suffers. For, be the will ever so good, impossibilities are not to be surmounted. Of such mischievous consequence are the arbitrary proceedings of those persons in the country, who say, ‘they fight with the temples.’ But that war is the gain of those who oppress the inhabitants: and robbing these miserable people of their goods, and what they had laid up of the fruits of the earth for their sustenance, they go off as with the spoils of those whom they have conquered. Nor are they satisfied with this, for they also seize the lands of some, saying it is sacred: and many are deprived of their paternal inheritance upon a false pretence. Thus these men riot upon other people’s misfortunes, who say they worship God with fasting. And if they who are abused come to the pastor in the city, (for so they call a man who is not one of the meekest,) complaining of the injustice that has been done |79 them, this pastor commends these, but rejects the others, as if they ought to think themselves happy that they have suffered no more. Although, O Emperor, these also are your subjects, and so much more profitable than those who injure them, as laborious men are than the idle: for they are like bees, these like drones. Moreover, if they hear of any land which has any thing that can be plundered, they cry presently, ‘Such an one sacrificeth, and does abominable things, and an army ought to be sent against him.’ And presently the reformers are there: for by this name they call their depredators, if I have not used too soft a word. Some of these strive to conceal themselves and deny their proceedings; and if you call them robbers, you affront them. Others glory and boast, and tell their exploits to those who are ignorant of them, and say they are more deserving than the husbandmen. Nevertheless, what is this but in time of peace to wage war with the husbandmen? For it by no means lessens these evils that they suffer from their countrymen. But it is really more grievous to suffer the things which I have mentioned in a time of quiet, from those who ought to assist them in a time of trouble. For you, O Emperor, in case of a war collect an army, give out orders, and do everything suitable to the emergency. And the new works which you now carry on are designed as a further |80 security against our enemies, that all may be safe in their habitations, both in the cities and in the country: and then if any enemies should attempt inroads, they may be sensible they roust suffer loss rather than gain any advantage. How is it, then, that some under your government disturb others equally under your government, and permit then not to enjoy the common benefits of it? How do they not defeat your own care and providence and labours, O Emperor? How do they not fight against your law by what they do?7

…

Good questions. Unfortunately for Libanius, and the rest of the world, (I’m with Gore Vidal on this one), Theodosius’s subsequent laws make the answers to them quite obvious.

1Gaddis, Michael, There is no crime for those who have Christ: Religious Violence in the Christian Roman Empire, University of California Press, 2005, p. 210.

2This is the emperor who, in 390, as retaliation for an uprising against the local Magister Militum, exploded in a fit of rage and ordered what is now known as the Massacre of Thessalonica, in which several thousand civilians, men, women and children were killed, indiscriminately. The lowest contemporary estimate is 7,000, the highest 15,000 dead.

3Julian II “the Apostate”.

4Emperors Valentinian and Valens.

6This proverbial expression took its rise from the Mysians, who, in the absence of their king Telepbus, being plundered by their neighbours, made no resistance. Hence it came to be applied to any persons who were passive under injuries.

7Libanius, Oration 30: For the Temples (pro Templis), in Dr Lardner’s, Heathen Testimonies, Thomas Rodd in London, 1830, pp. 72-96.

Chapter XV.—Of Hypatia the Female Philosopher.

Chapter XV.—Of Hypatia the Female Philosopher.