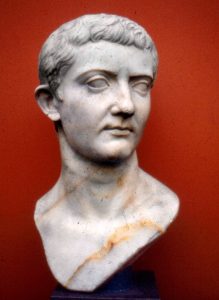

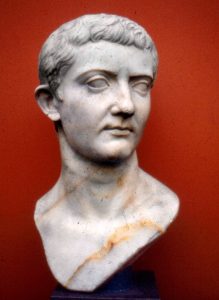

Bust of Tiberius. (Photo by Chris Nyborg)

Tiberius (Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus), November 16, 42 BC – March 16, AD 37, was the 2nd Emperor of the Roman Empire, and reigned from 14 AD to 37 AD.

He was, moreover, quite unperturbed by abuse, slander, or lampoons on himself and his family, and would often say that liberty to speak and think as one pleases is the test of a free country. When the Senate asked that those who had offended in this way should be brought to book, he replied: ‘We cannot spare the time to undertake any such new enterprise. Open that window, and you will let in such a rush of denunciations as to waste your whole working day; everyone will take this opportunity of airing some private feud.’ A remarkably modest statement of his is recorded in the Proceedings of the Senate: ‘If So-and-so challenges me, I shall lay before you a careful account of what I have said and done; if that does not satisfy him, I shall reciprocate his dislike of me.’1

1 Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, trans. Robert Graves, London: The Folio Society, 1964, pp. 126.

Roman aureus depicting Vespasian as Emperor. The reverse shows the Goddess Fortuna.

Vespasian was square-shouldered, with strong, well-formed limbs, but always wore a strained expression on his face; so that once, when he asked a well-known wit who always used to make jokes about people: ‘Why not make one about me?’ the answer came:

‘I will, when you have at last finished relieving yourself.’

… Yet Vespasian was nearly always just as good-natured, cracking frequent jokes; and, though he had a low form of humour and often used obscene expressions, some of his sayings are still remembered. Taken to task by Mestrius Florus, an ex-consul, for vulgarly saying plostra instead of plaustra (waggons), he greeted him the following day as ‘Flaurus’. Once a woman complained that she was desperately in love with him, and would not leave him alone until he consented to seduce her.

‘How shall I enter that item in your expense ledger?’ asked his accountant later, on learning that she had got 4,000 gold pieces out of him.

‘Oh,’ said Vespasian, ‘just put it down to “love for Vespasian”.’

With his knack of apt quotation from the Greek Classics, he once described a very tall man whose genitals were grotesquely over-developed as:

Striding along with a lance which casts a preposterous shadow,

– a line out of the Iliad. And when, to avoid paying death duties into the Privy Purse, a very rich freedman changed his name and announced that he had been born free, Vespasian quoted Menander’s :

O, Laches, when you life is o’er,

Cerylus you will be once more.

Most of his humour, however, centred on the way he did business; he always tried to make his swindles sound less offensive by passing them off as jokes. One of his favourite servants applied for a stewardship on behalf of a man whose brother he claimed to be.

‘Wait,’ Vespasian told him, and had the candidate brought in for a private interview.

‘How much commission would you have paid my servant?’ he asked. The man mentioned a sum. ‘You may pay it directly to me,’ said Vespasian, giving him the stewardship. When the servant brought the matter up again, Vespasian’s advice was:

‘Go and find another brother. The one you mistook for your own turns out to be mine!’

Once, on a journey, his muleteer dismounted and began shoeing the mules; Vespasian suspected a ruse to hold him up, because a friend of the muleteer’s had appeared and was now busily discussing a law-suit. Vespasian made the muleteer tell him just what his shoeing fee would be; and insisted on being paid half [of it]. Titus [Vespasian’s son] complained about the tax which Vespasian had imposed on the contents of the City urinals (used by the fullers to clean woollens). Vespasian handed him a coin which had been part of the first day’s proceeds:

‘Does it smell bad, son?’ he asked.

‘No, father!’

‘That’s odd: it comes straight from the urinal!’

When a deputation from the Senate reported that a huge and expensive statue had been voted him at public expense, Vespasian held out his hand, with:

‘The pedestal is waiting.’

Nothing could stop this flow of humour, even the fear of imminent death. Among the many portents of his end was a yawning crevice in August’s Mausoleaum.

‘That will be for Junia Calvina,’ he said, ‘she is one of his descendants.’

And at the fatal sight of a comet he cried:

‘Look at that long hair! The King of Parthia must be going to die.’

His death-bed joke was:

‘Dear me! I must be turning into a god.’1

1 Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, trans. Robert Graves, London: The Folio Society, 1964, pp. 291-293.

A marble bust of Caligula restored to its original colours. The colours were identified from particles trapped in the marble. (Photo by Marsyas)

Caligula had only a single taste of warfare, and even that was unpremeditated. At Bevagna, where he went to visit the river Clitumnus and its sacred grove, someone reminded him that he needed Batavian recruits for his bodyguard; which suggested the idea of a German expedition. He wasted no time in summoning regular legions and auxiliaries from all directions, levied troops with the utmost strictness, and collected military supplies on an unprecedented scale. Then he marched off with such rapidity that the Guards battalions could not keep up with him except by breaking tradition: they had to tie their standards on the pack-mules. Yet, later, he became so lazy and self-indulgent that he travelled in a litter borne by eight bearers; and, whenever he approached a town, made the inhabitants sweep the roads and lay the dust with sprinklers.

After reaching his headquarters, Caligula showed how keen and severe a commander-in-chief he intended to be by ignominiously dismissing any general who was late in bringing along the auxiliaries he required. Then, when he reviewed the legions, he discharged several veteran leading-centurions on grounds of age and incapacity, though some had only a few more days of their service to run; and, calling the remainder a pack of greedy fellows, scaled down their retirement bonus to sixty gold pieces each.

All that he accomplished in this expedition was to receive the surrender of Adminius, son of the British King Cymbeline, who had been banished by his father and come over to the Romans with a few followers. Caligula, nevertheless, wrote an extravagant despatch, which might have persuaded any reader that the whole island had surrendered to him, and ordered the couriers not to dismount from their post-chaise on reaching the outskirts of Rome – although wheeled traffic was forbidden in the streets during daylight hours – but make straight for the Forum and the Senate House, and take his letter to the Temple of Mars for personal delivery to the Consuls, in the presence of the entire Senate.

Since the chance of military action appeared very remote, he presently sent a few of his German bodyguard across the Rhine, with orders to hide among the trees. After luncheon scouts hurried in to tell him excitedly that the enemy were upon him. He at once galloped out, at the head of his staff and a few Guards cavalry, to halt in the nearest thicket, where they chopped branches from the trees and dressed them like trophies; then, riding back by torchlight, he taunted as cowards all who had failed to follow him, and awarded his fellow-heroes a novel fashion in crowns – he called it ‘The Ranger’s Crown’ — ornamented with sun, moon, and stars. On another day he took some German hostages from a military school, where they were being taught the rudiments of Latin, and secretly ordered them on ahead of him. Later, he left his dinner in a hurry and took his cavalry in pursuit of them, as though they had been fugitives. He was no less melodramatic about this foray: when he returned to the hall after catching the hostages and bringing them back in irons, and his officers reported that the army was marshalled, he made them recline at table, still in their corselets, and quoted Virgil’s famous advice: ‘Be steadfast, comrades, and preserve yourselves for happier occasions!’ He also severely reprimanded the absent Senate and People for enjoying banquets and festivities, and for hanging about the theatres or their luxurious country-houses while the Emperor was exposed to all the hazards of war.

In the end, he drew up his army in battle array facing the Channel and moved the siege-engines into position as though he intended to bring the campaign to a close. No one had the least notion what was in his mind when, suddenly, he gave the order: ‘Gather sea-shells!’

He referred to the shells as ‘plunder from the sea, due to the Capitol and to the Palace’, and made the troops fill their helmets and tunic-laps with them; commemorating this victory by the erection of a tall lighthouse, not unlike the one at Pharos, in which fires were to be kept going all night as a guide to ships. Then he promised every soldier a bounty of four gold pieces, and told them: ‘Go rich, go happy!’ as though he had been excessively generous.

He now concentrated his attention on the imminent triumph. To supplement the few prisoners taken in frontier skirmishes and the deserters who had come over from the barbarians, he picked the tallest Gauls of the province – ‘those worthy of a triumph’ – and some of their chiefs as well, for his supposed train of captives. These had not only to grow their hair and dye it red, but also to learn German and adopt German names. The triremes used in the Channel were carted overland most of the way; and he sent a letter ahead instructing his agents to prepare a triumph more lavish than any hitherto known, but at the least possible expense to the Privy Purse; and added that everyone’s property was at their disposal.

Before leaving Gaul he planned, in a sudden access of cruelty, to massacre the legionaries who, at news of Augustus’s death, had mutinously besieged his father Germanicus’s headquarters; he had been there himself as a little child. His friends barely restrained him from carrying this plan out, and he could not be dissuaded from ordering the execution of every tenth man; for which purpose they had to parade without swords or javelins, and surrounded by armed horsemen. But when he noticed that a number of legionaries, scenting trouble, were slipping away to fetch their weapons, he hurriedly absconded and headed straight for Rome.1

1 Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, trans. Robert Graves, London: The Folio Society, 1964, pp. 172-174.