Bad Bishop

For those who live agelessly in the shadows of the world, sustained by blood, history is not something that happened to other people. In twelfth century Europe a web is spun in those shadows to contain the ambitions of an immortal emperor. But, when history is a memory, the greatest danger comes from what has been forgotten.

Excerpts:

Incipit

Bad bishops protect good pawns.

– Grandmaster Mihai Șubă

For the subtlest folly proceeds from the subtlest wisdom.

– John Webster, The Duchess of Malfi (II,i)

Incipit narratio feliciter velim

3 August A.D. 1120

‘Break it in,’ Gratian commanded, and a tall man with a sword hanging against his hip did as he had been ordered. He put his shoulder up against the door and gave it a single push. The door, and lock, burst open; and a large wooden shard from the door frame exploded inward. Gratian thrust past him into the room, followed by two others, a man and a woman, and he froze. He stared at the man’s body, sprawled on its back and hanging half off the bed, at the great, dark pool of blood gathered on the floor beneath it, and at the severed head lying several feet away and in a little dark pool of its own. Gratian staggered.

And then he sank to his knees.

Behind him, the woman dragged her eyes with difficulty away from the corpse, and for a moment stared at the closed and bolted shutters of the two windows in the room. Then she turned to the man that had walked in with her.

‘Fetch Nicodemus,’ she breathed. As Clemens raced away down the hallway, she turned to the one that had broken in the door. ‘No one leaves, and no one enters these grounds, until I tell you otherwise. No one,’ she instructed. The man nodded, eyes grim, lips set in a slim, tight line. ‘Except Nicodemus.’ He nodded again. ‘Go see it done, and send me Flodoard. None but he is to come upstairs until I say so, or Nicodemus arrives.’

As he too hastened away, Livia raised her eyes toward the ceiling. She appeared not to be truly seeing it, for her gaze was trained somewhere infinitely far away, or towards the depths of her own mind. She blinked a few times, as though to clear her eyes, she drew a deep breath and turned round once more.

Gratian was still on his knees; still staring at the mutilated body.

‘How…?’ he breathed. It had been for himself to hear, not for her. She moved towards him. ‘Who…?’ Livia laid a hand on his shoulder and gently grasped his arm intending to coax him to his feet.

‘Come,’ she said softly. ‘I have sent for Nicodemus.’

Gratian appeared not to notice she was there. ‘Who…?’ he murmured again.

‘Come…’

He suddenly snatched his arm away from her grasp, though he still stared, like a man that all of a sudden has found himself in the middle of a dream, a terrible, bewildering nightmare.

‘Find me the one who did this,’ he said, and his voice was different now. He leapt to his feet. ‘Find me the one who did this!’ he roared.

Many miles away, more of them than any man, on foot or on horseback, could possibly have hoped to have covered in a mere three hours, a man was crouching by a stream, its surface rippling as though with quicksilver in the moonlight. He was washing clean the bloody blade of a dagger. He washed it meticulously, before he appeared satisfied. He dried it on the hem of his garments, and sheathed it, and placed it on the ground by the bank. Then he straightened up, and stripped, pulling the garments off over his head.

His chest, all the way down to his belly, and his back, were both riddled with strange, complex designs tattooed onto his skin, though the patterns were old now and faded. And the dull, brownish ink seemed to have been carved into his skin with a red-hot razor, for the gentle swell of ancient scars followed the intricate designs everywhere. He crouched down again, naked now, dipped his clothes into the stream and began washing the fine spattering of blood from these too.

No one would notice it. As no one noticed him. But he could smell it. And he did not wish to have the scent of the blood of the man he had killed, not three hours earlier, on him. He had taken no pleasure from doing so, or amusement, nor even pride. Though neither did he feel guilt. And the mild regret he had felt had lasted but a mere moment.

It had been necessary it be done, so he had done it.

They would have found him by now, he considered, as he washed the man’s blood away from his clothes. He regretted their grief; but that was the way of the world – of life, and of Time. It brought many things with it, and took them away again. He was merely a part of this interminable cycle. As was everyone else.

Introitus

Amarante had skin fair and pale, but for that creamy tone which suggested that, had the sun ever been allowed to caress it for long, it would have darkened to a rich, warm bronze. Her eyes had the deep amber colour of honey and her hair, when loose, reached the small of her back in great, dark waves. When she had been a child, her mother had often said, as she had brushed and braided her daughter’s hair, that it had the colour and lustre of ebony. Her father had jested that it was as black as a crow’s plumage. Though her mother scolded him for saying such things about his beautiful daughter, Amarante herself had never thought the comparison unflattering; for a crow’s plumage, she felt, had a lustre that far outshone both ebony and jet. If a woman’s hair was for her appearance akin to fine jewellery, then Amarante was blessed with untold riches.

She was born in the city of Toledo, in the year of the Lord 1080. Her father was a physician and scholar of Mozarab descent. Her mother, uncommonly, was Greek. Her father had married late in life, having spent his youth travelling and studying. It had been an ambition of his to visit as many of the greatest libraries and universities of the world as life would allow him to. He had travelled to the east, to Fez, Cairo, Baghdad and Constantinople. And on his travels, aside from wisdom, knowledge, and a wealth of books, he gained a wife. Amarante’s mother hailed from a family of wealthy and well-educated merchants who, despite the difficulties posed by such an unusual match, were sufficiently impressed by their daughter’s suitor, by his standing, education and refinement, that they gave their blessing – along with a substantial dowry.

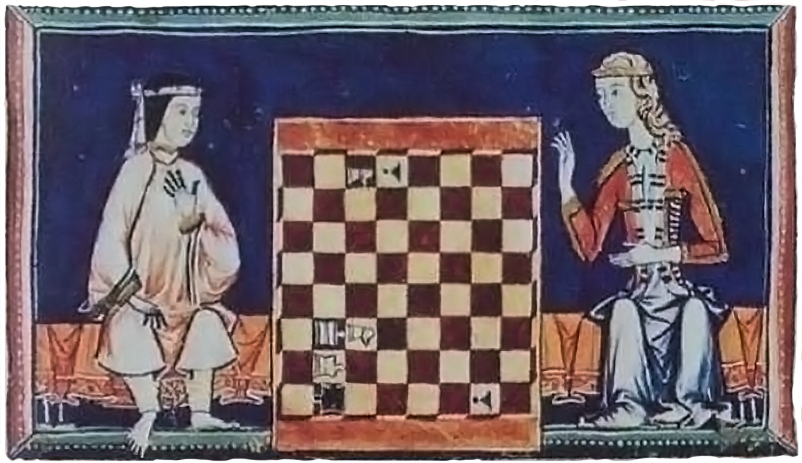

As a child, Amarante thought that Toledo was the most beautiful city that could exist in the world. The streets were paved, and lit at night; there were baths, mosques and churches, libraries and hospitals. The houses were built of stone and marble, they had balconies and garden courtyards, with trees and flowers and fountains. Muslim, Jewish and Christian scholars often congregated in each others’ houses to read and compose poetry, relate stories, discuss the philosophies of the Ancient Greeks and the Romans, and to play chess.

After the fall of Toledo to the Christians in 1085, scholars from the Christian kingdoms began arriving, lured there like moths to a candle-flame by the famed libraries of the city and the treasures they held hidden. Most of these treasures were written in the Arabic tongue, in Hebrew, and even in Greek, and the Christian scholars had need to translate them into Latin, before the wisdom and knowledge they held hidden could be unlocked. For decades, Muslim scholars, Arabized Christians and Jews met at the Christian courts to achieve the translation of these books, and Amarante’s father was one of them.

Over the years, in Toledo, his already large personal library had grown in size even further, and it was not infrequently that visiting scholars would appear on their doorstep, requesting access to the library, so well known had it become in the city for its wealth. He never refused anyone and so Amarante grew up surrounded by men of learning and books.

It had been her mother who had first undertaken her daughter’s education. By the time she was eight, Amarante could speak, read and write both Arabic and Greek, and, of course, Castillian. Then, her father determined that she should also learn Latin, geometry and mathematics, music, calligraphy, and chess. Chess he taught her himself, for she had immediately shown an uncommon aptitude and love for the game. For the rest, her mother hired tutors. They all came to their home on different days and different times, but it soon became apparent that the child was more than commonly gifted in learning, and engaged in it with rare dedication and enthusiasm. Eventually even her father noticed. And when he did, he took over the task of instructing her himself.

In retrospect, it was clear to Amarante that her farther had been hoping that he might sire a son to whom he could impart what he knew, a son that perhaps would grow up to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a scholar and physician. Her mother had indeed given birth to a son, but the child had died not two months later. After she miscarried a second male child, Amarante’s father gave up hope for a son, and decided to teach what he could to the child he already had. He was already advanced in years and was eager perhaps to impart his knowledge to someone, even if this was to a daughter and not a son. That is not to say that her father did not love and care for her. Amarante had nothing but the warmest memories of her father. He lavished attention on her in ways other fathers rarely did their daughters.

When she turned eleven, her father began teaching her the basics of astronomy, and two years later, medicine. She would never be able to practice the profession, but the relish she took in learning, her love and her apparent aptitude in the subject motivated and inspired her father to continue teaching her what he knew.

Eventually, inevitably, her mother and father decided that it was time she married. She was already eighteen. Though Amarante felt no such inclination herself, refusing to do so was impossible. She was fortunate in that her parents were greatly forbearing and for a long time took her objections to heart. By the time she was twenty she was still unmarried, and was still spending her days reading, studying, and playing chess.

At length, however, she was forced to capitulate. Her father was old and ill, and she did not have the heart to refuse him any longer. She was married at the age of twenty-one to a physician, a widower, twenty-five years her senior. Her father gave her a dowry to rival the one her mother had received. Like her mother’s, her own dowry included a multitude of books and rare manuscripts from her father’s library that, on their own, amounted to a large fortune. He died the following year.

In her new life, Amarante was once again fortunate. Her husband had few demands of her and, as a man of letters himself, he did not object to her uncurbed enthusiasm for learning. She would often play chess with him, or read to him. He always said that he loved listening to the sound of her voice. Over the years she came to care for him, it was impossible not to, for he was a good man. They bore no children, and there were none from his previous marriage. It had been assumed that his first wife had been barren, yet the continued sterility of his second union suggested that the fault had not lain with her, after all. He was an excellent physician, but not even he could cheat fate. He died, late in 1105. As they had no children, and he had no other living relatives, Amarante inherited the bulk of his estate, as her mother had inherited her father’s estate after his death. Deciding that it was impractical maintaining two households with only just the two of them left, she rented out her husband’s properties and moved back into her family home, adding her husband’s library to that her father had left behind. Her father’s library had never ceased attracting visiting scholars and, with the addition to it of her husband’s collection, it had now become truly impressive.

Her mother died in October 1106, and at the age of twenty-six, Amarante was left alone in her childhood home, with several servants, and what was now her library. Her mother had beseeched her, before she died, to marry again, and she had promised that she would. She had no plans to, but how could she deny her mother the comfort of such a promise? Perhaps one day. Having someone to play chess with again would be nice.

Chapter I

A.D. 1106-1107

It was early one evening in December of that same year that one of Amarante’s servants announced to her the arrival on their doorstep of yet another two scholars requesting access to the library. Because of the time of year, it was already beginning to grow dark outside, but the hour was not yet late so she instructed the servant to show them in. She was following her father’s example and gladly allowed access to the library to all who requested it. Knowledge was to be shared and disseminated, not hoarded and hidden. She asked the servant to show the visitors into the reception room where they could wait for her, while she changed out of her indoor clothing and into something more appropriate. Although of the Christian faith, her family had never completely abandoned the Arabic customs.

She had never been partial to bright colours, usually preferring hues of dark green and blue, yet after the death of her husband she had taken to wearing black or indigo, as was the custom. That day, she decided on an indigo cotte, and a black bliaut, one of three she had had made over the past year. Though not strictly necessary, she chose to also cover her hair with a fine, silk veil, held in place by a plain circlet. She had no wish to horrify what would doubtless be two Christian monks, priests, or at least deacons – they usually were – expecting to meet a respectable widow. Likely, they were expecting to see someone her mother’s age.

That all the scholars arriving from the north in search of old, forgotten books, almost without exception, were churchmen, was still something that caused Amarante to marvel. It had been different, she still remembered, when she had been a child, and the scholars that frequented their house had not been from the north, but from Al Andalus.

She arrived with two attending servants to greet her visitors in the reception room and was quietly surprised to see, not two churchmen, but two lay-scholars awaiting her – both clad in the Christian style. One was standing over her chessboard clearly in contemplation of the game she had been playing with herself, while the other stood patiently in the middle of the room, awaiting her arrival. His garb was ungirt and long, almost touching the floor, as noblemen sometimes wore it, with the embroidered neckline and hem of his chemise visible under the purple bliaut of silk damask with its long, wide sleeves. He seemed the elder of the two, having seen perhaps forty-five years of life, she gauged. Perhaps a fraction less, perhaps a fraction more, for it was difficult to tell. He was clean-shaven and, though with age his hairline had receded somewhat from his temples, his hair was still dark, silken and long, and fell loose to below his shoulders, almost to the middle of his back. His complexion was of the olive, southern hue, but seemed pale, as though he had spent his life inside a dark library and had not seen much of the sun in years. He was of a middling stature and likely of a lean frame beneath his loose, flowing clothes; and his dark blue eyes were at once deeper, and more piercing, than any Amarante had ever before seen; they shone blue like the colour of the Middle Sea under a midday sun, and seemed to harbour depths as great as the ocean itself.

As Amarante walked into the room, the man’s companion looked up from the chessboard. This one’s dress was simpler, the neckline and hem of his chemise more conservatively embroidered, though both this and his brown surcotte were of finespun fabric of the highest quality. Both garments were shorter than the elder man’s, reaching his mid-calf, and were girt, low on the waist, by a brown leather belt with a long tongue that reached the hem of the surcotte. His full-length mantle, of a deep, tan colour, was clasped on the right shoulder with a plain, silver, ring-brooch.

A man perhaps in the middle of his third decade of life, she judged, the faint creases of expression on his face somehow ageing him less than one may have expected. The severity they lent his appearance seemed rather as an integral part of his character, than a product of age. He was clean-shaven, his skin had the pallor of fine alabaster, his unruly, blond hair was cropped short, and his deep-set eyes were of a colour Amarante had never before seen; grey – like an overcast winter sky. A Frank, or a German. It had seemed to her the man could have hailed from no other part of the world.

The elder of the two inclined his head and introduced himself.

‘Δέσποινα, ὀνομάζομαι Ἀτρεύς. I am told you speak Greek,’ he said, fluently and with no perceptible accent, in her mother’s tongue. Such was her surprise at hearing Greek spoken so effortlessly, that she hardly noticed that the man had offered but his given name, Atreus.

‘I do,’ she replied, making no effort to conceal her surprise. ‘I am Maria Amarante Assaraff. You are welcome in this house, sir. …But we could continue our conversation in Latin, or Castillian, if it would be more convenient for you or your companion,’ she suggested.

It had seemed to her that the likelihood of the northerner speaking Greek was akin to the likelihood of the sun not rising the next morning.

‘My name is Kyrus, my lady. Forgive me for not having introduced myself, but I did not wish to interrupt. It is not necessary to converse in Latin on my account,’ the younger man said in Greek that, despite the faintest of accents, left not much to be desired.

Barely succeeding in concealing what was now astonishment, Amarante inclined her head to him.

‘Forgive my assumption, sir. It is not often that I encounter people that speak my mother’s tongue here,’ she said.

‘It was a reasonable assumption, my lady. You need not apologise.’

‘And your name, sir, I cannot help but mark that it is not of Frankish origin. Though it does occur in the Bible, it is uncommon, and I can only assume that you were named by a scholar. Unless you have Persian ancestry?’

‘You are very right, my lady. On both counts,’ the man said, and he glanced at his companion.

‘My lady, as you no doubt have been informed, we are here to request access to your library. Your, and your father’s, reputation of unparalleled hospitality to scholars from every corner of the world is far-reaching, as is the fame of the treasures your library holds,’ said the Greek.

‘I fear I am unworthy of such high praise, for it is my father’s, mother’s and late husband’s efforts that have resulted in this great collection of works, and not mine. I but follow my father’s example in allowing access to these works, as the books may be my property, but the knowledge held therein is not. As I have benefited from this treasure, I wish others to. You are welcome to study the contents of the library, for as long as you wish. And if I can be of any assistance to you, please do not hesitate to ask. To my knowledge, the works contained there are mainly in Arabic, but also in Greek, and a few in Hebrew. I myself do not speak Hebrew, but if there is any assistance you require with the Arabic, I am at your disposal. I would beg you also to remain, as my guests, if you have not already made other arrangements…’

‘You are too kind, my lady,’ Atreus said, ‘but we already have other accommodation in the city. We would only ask for your leave to return at your earliest convenience to begin work.’

‘You are welcome to begin any time, even tonight, if you wish it. I shall show you to the library and leave one of the servants with you for anything else you might require.’

The Greek once again inclined his head. ‘Your graciousness is humbling.’

‘It is but my pleasure to assist, sir,’ said Amarante and motioned to the servants to follow, as she showed the two visitors to the library. She left a servant with them and withdrew upstairs to her rooms. Before retiring for the night, she asked a maidservant to see whether the two men were still in the library, and when she was informed that they were, she instructed that one of the servants remain at their disposal until they left, and if they returned the next day, to be allowed in again.

She was informed the following morning that her visitors had only left around the hour of midnight, after the church bells had tolled for matins. They returned late that same afternoon, and continued in this manner for two weeks. She had been intrigued at the time by the strange hours they kept, but had ascribed it to the fact that scholars sometimes had unusual habits, and had made no comment. After all, she too enjoyed the quietness of the night-time and often stayed up late, reading or studying. Occasionally, she encountered them, mostly as they arrived, or if she entered the library herself to retrieve a book or a scroll, but for those two weeks that was the extent of their interaction.

Until one evening, a servant sought her out in her study, the room that had once been her father’s study, to inform her that her visitors wished to speak with her. She received them there, where she worked, her desk laden with open codices of Dioscourides’s Περὶ Ὕλης Ἰατρικῆς, Ibn Juljul’s commentary on Dioscourides, Ibn Al-Wahshiya’s Book of Poisons, Abu al-Qasim’s The Method of Medicine, Al-Tamimi’s Materia Medica, and Al-Razi’s Kitab sirr al-Asrar. The two men seemed unsurprised to see a woman thus engaged and they showed what she took to be a courteous interest in her work, before explaining the reason they had asked to see her. The Greek, it appeared, wished to thank her for her welcome and forbearance, and take his leave, for he had certain matters to attend to and would be leaving the city for a couple of weeks. Yet he begged leave to return, when these matters had been seen to, and the German, for his part, begged leave to remain and continue with his work, until his companion returned.

Amarante assured them both that they were welcome to remain for as long as they wished, or return, when they wished, and, once more thanking her graciously for her hospitality, the two men retreated from her study and left her to her work.

A week later, the German was still coming and going, in the same manner as before, and yet she had barely laid eyes on him more than once. And then, late one evening as she sat in the reception room, wiling away the time with a solitary game of chess, the man appeared at the open doorway.

‘Madam,’ he said, in his usual, even baritone, addressing her as always in Greek. Amarante raised her head, only mildly surprised that she had not heard him approach. In his left hand, he held an ancient-looking scroll. ‘Forgive the intrusion,’ he continued, ‘but I fear I am in need of the assistance you so graciously, earlier, offered.’

‘Do not speak of it, sir. It is no intrusion,’ she said, with a smile, and motioned to him to enter and take a seat. ‘You have found something of interest?’ she asked, gesturing lightly towards the scroll.

‘It seems so,’ he responded, handing her the ancient thing, ‘but I am afraid this form of Arabic goes beyond my ability to, with any confidence, read it.’

As he spoke, Amarante carefully unfurled the scroll, and considered its contents.

‘It is no wonder, sir. This is a very old Arabic script, and without most of the diacritical markings, it will be a challenge even for me. …I confess that I do not recall having seen it before…’

‘I would not find that surprising, madam. It was at the very bottom of a chest filled to the rim with scores of other scrolls, papyri, and loose leaves of parchment. That I came across it was largely a matter of chance.’

‘I suspect that you unearthed it from one of the chests that comes from my late husband’s collection, sir. And with that, I admit, I am not as familiar as I am with the collection my father put together. …Well, it is an alchemical work, dealing, from what I can see, mostly with minerals, but I have no doubt you have ascertained that already. It is, I fear however, a fragment…’ Amarante concluded and raised her eyes to him once more.

‘I suspected as much, also.’

‘Do you still wish it translated?’

‘I would be grateful for your assistance.’

‘And I would be glad to give it,’ Amarante smiled at him. ‘But I must warn you that the marginalia are beyond my abilities as well, for they are not in Arabic, but Pahlavi, and that I cannot read.’

‘It is no matter. Your assistance with the Arabic is already more than I could have expected. No doubt, when he returns, Atreus can have a look at the marginalia. He speaks Persian and I know he reads Pahlavi script.’

‘We should begin, then,’ said Amarante, and called one of her maidservants. ‘Jasmín, bring us some wine, but first fetch me some tablets, parchment, pens and ink from my study,’ she instructed.

That evening, they worked well into the night, Amarante cautiously reading and translating the ambiguous scribbles, and Kyrus, as a scribe, writing down her words. It was a challenging endeavour, and circular, for much of the interpretation needed rely on context, and context could only be determined through the interpretation of the script. Often, she would have to go back and correct her initial reading of words, after later context suggested that the vowels she had assumed to be intended, but not marked, were in fact other vowels – and a different word. She translated into the first language that came to her mind, and the most appropriate word, sometimes into Greek, sometimes into Latin, without taking the time or effort to be consistent. Merely reading the script and understanding it was difficult enough, without this additional consideration, and the German seemed not to be troubled by the inconsistency. Whether she translated into Greek, or Latin, he wrote down all directly into Latin.

At length, Amarante pleaded exhaustion, and asked that they continue the following day. Jasmín, sitting quietly in a corner, had long since nodded off.

Kyrus apologised deeply for being so inconsiderate and keeping her awake until such an inhumane hour, but she waved his apologies aside. It had been one of the most pleasant and interesting evenings she had enjoyed in years.

The following evening, they continued in much the same manner, for more long hours, and again the evening after that. And still, progress was slow.

‘My father once told me that one can only read old Arabic script, if one already knows what is written there,’ said Amarante with a smile, one evening, after considering how much there was still to translate, and how comparatively little they had thus far succeeded in deciphering. ‘I fear he was not far mistaken.’

‘We are fortunate, then, that you already know what is written there, madam, else the endeavour would have been hopeless,’ said Kyrus.

‘Not at all, sir, I assure you!’ said Amarante. ‘I have never before laid eyes on this work.’

‘But you are exceedingly well-versed in the arts it expounds, and hence are able to descry its meaning, despite the script’s ambiguities.’ He turned a level gaze to her that carried no hint of irony, only categorical assurance.

‘You flatter me, sir.’

‘Not at all. It is not in my nature to flatter,’ said the German. ‘Someone unversed in alchemy would have been unable to read this work, let alone translate it in any meaningful way.’ He paused for a moment, then quite simply asked, ‘Do you also practise the art, madam, aside from studying its theory?’

‘I… dabble, sir,’ said Amarante, ‘in the arts my father saw fit to teach me.’

Kyrus stared into her eyes for a moment, then, turning his gaze back to the leaf of parchment in front of him and picking up a pen, declared:

‘I would be very surprised if all you do is to dabble, madam. … If you would not be averse to it, I would be very much interested in seeing where you work and perhaps talk at greater length about your work, while I am still here…’ he concluded, as he dipped the pen into the inkwell.

‘…I have no objections, sir, if that is what you wish,’ said Amarante, ever so slightly startled.

‘It is,’ said Kyrus, and raised his eyes to her in calm expectation, his pen held poised and ready over the parchment, waiting for her to once again begin translating.

The following evening, during a small pause for rest from the endeavour that she had begged for, Amarante showed him the small workshop that her father had used for the preparation of his medicines, and that she now counted as her own. Kyrus looked around the place with dispassionate yet astute interest and, for some little while, talked with her about her work. In the end, and as they were leaving the workshop to return to the reception room and their translation, he calmly announced that he could think of no worse crime than the restrictions imposed by society on a mind like hers.

‘Wasting a gift like yours, madam, would be blasphemous to any god,’ he said.

‘Surely you overestimate my abilities, sir,’ she replied.

‘Not in the least. I assure you,’ he responded, but what he had just said had made something stir, deep in her mind. She had heard those words before, somewhere, and she was still striving to remember where she had perhaps read them, while she continued reading, and translating, and the German continued writing down her words, for another couple of hours.

That night, when Kyrus had taken his leave and she had finally retired to her bed, Amarante shut her eyes and the answer suddenly came to her. She remembered where she had read that sentence before. Her eyes flew open, for a moment she remained lying there, staring into the darkness then, she leapt out of bed, hurriedly lit a small lamp, and ran to the library. She rummaged through cabinets and chests full of books, and her search lasted some good while, yet, in the end, find the book she did. She opened it and read the few lines written there with heart pounding loudly in her chest. It was an Arabic translation from the original Latin of a treatise on Ethics and the Nature of Evil, written in the year 929 by one Kyrus of Ulm.

Amarante sat down on the nearest seat and stared at the book. Then she read the entire treatise again, from beginning to end, seeking to make certain that the words she remembered were indeed to be found in this work. Having confirmed to herself that she was not mistaken, she closed the book and placed it back at the bottom of the large chest where she had found it. Then she reclaimed her seat and stared at the flame of the oil lamp she had brought with her and under whose meagre light she had read the book. The book had been part of her dowry, originally having come from her father’s collection. The Arabic translation had been made in 980. And as Amarante sat there, she wondered what the likelihood might be of two, unrelated German scholars, bearing the name of Kyrus; and found it to be more than improbable. Considering that this essay was almost two hundred years old, she concluded that it must have been written by the great-great-grandfather of the Kyrus she knew. This would also easily explain how he had been able to quote from it, virtually verbatim.

She resolved to ask Kyrus, the next day, which part of Germany he hailed from. And then it struck her that it would not be the following day, but today, for the sun would soon be rising. It was time she returned to her bed and slept. Though still alert, she was tired, and it seemed likely that she would have yet another late night that day as well. The German never appeared before the late afternoon. No doubt he had other business during the day, though she had never enquired as to what this was.

The following evening, as she had resolved to, she put her question to Kyrus. She was hardly surprised, though she did endeavour to seem otherwise, when he responded that he originally hailed from Ulm. She told him that she had read an essay on Ethics and the Nature of Evil by one Kyrus of Ulm – something he had said the previous night had reminded her of it – and she asked him whether he was in any way related to the scholar that had written that wonderful work. His head had snapped up then, and his grey eyes had become sharp and piercing like steel, and for a moment she had felt as though he had looked right through her skull and into the deepest recesses of her mind. It was only a moment, then his gaze reverted once more to its usual reserved astuteness.

‘You have read that work?’ he asked.

She nodded.

‘There is an Arabic translation of it in the library.’

He appeared surprised at the revelation.

‘I was not aware that it had been translated,’ he said. ‘Yes, it was written by my great-great-grandfather.’

‘Clearly, sir, your name carries with it an excellence in scholarship,’ said Amarante. ‘Do you happen to know where the original lies?’

‘I own it,’ he replied. ‘And there is a copy in Constantinople. I can but assume that whatever other copies may exist have come from that one.’

‘I would have dearly wished one day to read the original. So much is lost in translation sometimes and in a work such as this one there are so many fine nuances of meaning. But it seems unlikely that I will ever travel as far as Constantinople.’

He took a moment before responding.

‘I would gladly have offered you the original to read, but unfortunately I do not have it with me in Toledo,’ he said, in the end.

‘You are most generous. I did not mean to suggest that I could have borrowed something as precious as the autograph.’

‘Madam, if the work interests you, I would happily have loaned you the original. But as that does not seem possible, you have my word that, once I return home, I will have a copy made, and send it to you. It is the least I can do to thank you, for your invaluable assistance, and your unprecedented hospitality.’

‘Sir, that is too much to ask of you! You are far too generous! I could not possibly accept,’ Amarante exclaimed. To have a book copied and bound was an enormous expense. And then to have it sent, with the risk that it may be lost or stolen along the way…

‘I insist. Please do not refuse this very small gift,’ he said, simply.

It was far from a small gift and Amarante knew it well, but it was impossible to refuse, so it was left at that, they spoke about it no more, and continued with their translation. Two weeks went by, and at the end of them, the Greek, Atreus, returned. Another two weeks passed before the translation from the Arabic was complete, and then Atreus, with impressive ease, translated the Persian marginalia. Finally, early in February 1107, they both thanked her once more for her hospitality, and departed.

Once they had left, Amarante took the time to copy the troublesome work that had taken so long to decipher and translate, into a modern, and rather more legible, Arabic script. When this endeavour too was completed, she put the work aside, and returned to her usual routine.

Three months went by in this manner, and then one day in the middle of the month of May, a messenger arrived at Amarante’s door, handed Jasmín a cloth-covered and carefully wrapped parcel for the mistress of the house, and left. When Amarante opened the parcel to find a letter and a book, she thought she knew what it was, though how it could have arrived so swiftly she could not imagine. It took many months to copy and bind a book. Sometimes as long as a year and a half. She had begun breaking open the seal of the letter when it struck her. This was an old book. There was no need to even open it, for it was perfectly evident. It was in excellent condition, yet still, the dryness of the leather binding and its slightly brittle, yellow pages betrayed its age. This book had not been written, or bound, recently. She dropped the letter unopened and opened the book instead.

Incipit liber de morum et ingeniorum mali Cyri Hulmae feliciter, Amarante read with gradually rising heartbeat. She ran her fingers over the yellowed, brittle parchment and carefully turned over the page. The ink was dull and faded, not glossy and bright like fine silk, as fresh ink should be. She read a sentence here and a few sentences there, as she turned over the pages. To the very last page she turned, and read the explicit. The ink was the same throughout; old and faded and brown. There were pages where faint smudges had been created over the years on the edge of the page, as one would have repeatedly thumbed through the book. And the script, it struck her, was not what she would have expected to see, even allowing for the small, inevitable, variations in regional style of the scribes. Ever so slightly, the script leaned towards the left, she noted. A scribe that favoured the left hand? Unusual, but hardly important. What was important was that this script was smaller than what was common. Though still cursive, it had a faintly oval, rather than round shape to it, with long and straight descenders and ascenders. And all these ligatures…

There was no doubt in her mind. This was no recent copy. This was the original.

She grabbed the letter and opened it, her eyes swiftly darting over the fresh, silky, black script of recent ink.

Cyrus Hulmae, nobilissimae mulieri Amarantae Assaraff. Salutem. I can only hope that this small gift will go some way in repaying your unprecedented hospitality and generosity.

Nonae Maii, Anno Domini MCVII

Though she read the letter three times before she had satisfied herself that she had read it correctly, a nagging inkling of doubt remained in her mind, and Amarante returned to the book. Surely she must have been mistaken the first time. This could not be the original. She took one look at it and immediately knew that it was. Her entire life she had spent surrounded by old books. She could recognise a two hundred year-old book with less effort than she had expended on this one. Amarante read the letter again. Then stared at the book again.

And then something else began troubling her, tugging at the very back of her mind, but at first she found she could not place it. Very gradually, like an emerging figure rising up out of the dark waters of an ocean, realisation dawned on her. It took some few moments before she could with certainty say that it was not merely her own imagining – and for those few moments she forgot to breathe. Carefully, slowly, Amarante picked up the letter and laid it down next to an open page of the book, motionless, staring at the two until her body forced her to gasp for breath. Only then did she realise that she had not been breathing.

It was the same hand.

There was no doubt.

The hand that had written that book and the hand that had written that letter were one and the same.

Amarante suddenly leapt up and ran to the library. She first went through the wax tablets that were always available there, then began riffling through every loose leaf of parchment, and every scrap she could find. Her breath caught in her throat when, against all reasonable expectation, she found what she had been looking for; a small fragment with a sample of the German’s handwriting. She grabbed it and ran back to the book and letter. The letter… the letter could have been forged, for what reason she could not even begin to glimpse, but it was possible. What she was holding now though, no; this could not have been forged. Her hand shook slightly as she placed the scrap of parchment from the library, carefully, next to the book’s open page.

She stared at them and, all of a sudden feeling quite weak, she sat down heavily on the nearest seat. She blinked, looked away, and waited a few moments until she felt that her mind had cleared sufficiently, and then she considered the evidence again – carefully, meticulously, comparing each word, letter for letter. It was unnecessary, for she already knew, but she needed do it nonetheless.

The ‘a’s, all of them, were open at the top, the ‘g’s were mostly of the open form too, the ‘p’s had a tiny wedge at the top of the long and straight descender whereas the ‘q’s did not, and the ‘x’s had an oblique, elongated descender on the right. But the most unmistakeable sign were the ligatures. The letters e and n were ligated, as were the letters e and c, e and r, and e and t, resulting in a slightly strange spacing of the words and altering the appearance of the letters.

And everything leaned slightly towards the left.

It was the same hand.

She had spent weeks watching the German write, as she translated. How could she not have noticed the peculiarities of his hand before? This was an antique style of script that she had only ever seen in a few theological works originating from northern Europe that were kept in her library. All were well over two centuries old.

Here was a conundrum Amarante knew she could not solve through logic. She knew, with convinced certainty, that the book she was holding was over one hundred years old, likely, closer to two hundred. Neither did she have any doubts about the hand. Yet, it was simply not possible that the man she had met had written both book and letter. For that would mean that he had already seen two centuries of life.

Knowing that she was not mistaken, yet having no other hope for reason returning to her world, Amarante, book in hand, and with Jasmín in tow, went that day to visit an old friend of her father’s that was still alive. He was a scholar and a poet and had an extensive library of his own, and he too had spent his life surrounded by old books. Amarante told him that she had acquired this book from an itinerant merchant and she asked if he could date it for her. He took his time, examining the book carefully, its binding, each page of parchment almost individually, the ink, he read portions of it, and finally he gave his verdict: Over one hundred and fifty, likely, closer to two hundred years old. Amarante thanked him for his time and returned home.

She had been right about the book, and she knew that she was not mistaken about the hand. The sole remaining explanation was beyond even contemplation. At least that day. She put both book and letter in a small chest, and resolved not to look at them again until the day after.

The day after offered no more acceptable conclusion than the one the previous day had offered. Neither did the day following; or the one following that. And during this while, Amarante had had cause to think back, and remember, and consider again all that had struck her as curious about her two visitors. Eventually, unable to do otherwise, she realised that she was beginning to accept this, most absurd, of notions. By the end of the week, she had accepted it, had decided to count it as one amongst the many mysteries of life, and herself fortunate to have had this strange experience. She resolved to keep the book and letter always close, to remind herself that the things man did not know about the universe were infinite and that she should work night and day to understand as many of them as possible.

That same day, she awoke from a deep sleep, in the middle of the night, wondering what it had been that had woken her. She opened her eyes and waited a moment for them to adjust to the silvery dimness of the room. The light of a waning gibbous moon near its zenith was spilling in through the slits in the shutters. Still perplexed, but now wide-awake, she turned her head, and saw that there was something lying on the pillow beside her. A small, folded note. It was on paper, she noted, as she sat up in bed and picked it up, not vellum or parchment; a rarity indeed. Hastily, she lit a lamp and unfolded it.

She recognised the hand immediately. She had spent a full week staring at this hand. All it said was:

The White King’s Knight to His own third House.

Despite herself, Amarante’s stomach contracted painfully as she read; not out of alarm; or even of surprise. She was singularly unsurprised, and entirely without fear, she realised. Fear would have been absurd. The man, or creature, whatever he turned out to be, had spent the better part of two months in her house. If he had had mischief in mind he had had ample time and opportunity to enact it. Any surprise she may have felt at reading the note had been almost instantly quashed by her mind, uninvited, yet most thoughtfully, reminding her that his letter, which had arrived with the book, had been dated the seventh day of May – barely ten days since. Clearly, he had arrived back in Toledo at the same time as, and most likely with, the letter. Yet still, some emotion, which she spared no time in pointlessly contemplating, had made her body react thus. Perhaps it was the same kind of thrill she experienced upon encountering some new knowledge, or concept; the thrill of solving the riddle. Of understanding.

And here, one riddle spawned the next and, no doubt, another one after that, and yet another one later, she thought, as she rose from her bed. The image of her chessboard, as it stood, in the middle of a long-standing game, rose clear to her mind. How had he known to choose the side whose move it was next? No one but she could have known that, she thought, as she dressed without haste.

Instead of wasting time wondering in vain about a multitude of other questions she would never receive answers to unless he so wished it, she chose rather to contemplate her next move on the game of chess he seemed to wish to play with her. She had no need to see the board to decide. She could easily remember the positions of all the pieces and envisage the move he had just made.

In the time it took her to dress and make her way downstairs to the reception room, she had decided. The black Bishop’s Pawn on the King’s side would move to square three. She opened the doors to the reception room and walked in, even as the German was moving the black Bishop’s Pawn to square three on the King’s side.

‘The game seems fairly evenly matched,’ he said, contemplating the board.

That he appeared to have read her mind before she had so much as approached the room was less surprising to Amarante now than it would have been to her a week earlier. She but glanced at the chessboard.

‘Appearances are often deceptive,’ she said.

‘I agree that this is often the case,’ he replied, without looking up, and moved his sole remaining white Knight to capture one of her black ones. ‘Your move.’

Amarante walked up to the board, captured his last Knight with a pawn, and then took a seat on the divan across from him.

‘Atreus believes that it will be at least twenty years before I shall be proficient enough in this game to beat you, madam.’ He considered the board for a moment and then made his move, capturing one of her black pawns with a white one. ‘That is, of course, assuming you do not improve in the meanwhile.’

She moved her Queen forward to Bishop’s square five on the King’s side.

‘And by then, you would be… two hundred and forty years old, perhaps?’ she suggested, bluntly.

‘Two hundred and thirty-four, to be precise.’

He moved his Bishop forward to threaten her Queen, and she retreated to Rook’s third on the King’s side.

‘He is likely right,’ said Amarante, in response to his earlier comment.

‘He also believes that he has a better chance against you.’ The German moved his single most advanced pawn even further forward, to King’s Bishop seven.

‘You may tell your friend that I would be happy to play against him whenever he has the time and inclination,’ Amarante said, considering the board. She moved her Rook forward to capture one of his Bishops and simultaneously threaten his Queen.

‘I shall certainly relay the message,’ said Kyrus. He stopped speaking for a few moments while he pondered his next move. He had been cornered, and would be forced to make a sacrifice. He chose to save his Queen. He captured Amarante’s Rook with a pawn, a move, which yet exposed his own King’s side Rook to capture.

Amarante took the white Rook with her Queen, which now stood, threateningly, on the same row as the white King, the only piece between the two being the last remaining white Bishop.

After brief but intense consideration, during which time she watched him in silence, Kyrus moved his Queen forward, to jointly threaten Amarante’s sole remaining Knight and a pawn on her King’s side. Both were enjoying the protection of other pieces, but at least he was distracting her from attacking his King, and placing her own King under some semblance of threat.

Amarante took a moment to think, then moved the threatened pawn forward, to stand immediately in front of the white Queen. It remained under threat, but it was also still protected, it limited his Queen’s agility in that end of the board and, if captured, would leave her own King more room for manoeuvre.

Kyrus moved his Queen to Queen’s side Rook six, and said:

‘Check.’

Amarante moved her King one square forward and out of danger, placing him between Knight, Rook, Bishop and pawn, whilst at the same time opening up the row for her Rook to move across, unimpeded, in any direction.

The German briefly considered the board, and then conceded defeat. Any move he made from this point on would but delay the inevitable. He gently knocked his king over and sat back in his chair.

‘I fear Atreus may be right. It will be a long time before I can compete with you, madam.’

‘The way I understand it, time is not an insurmountable problem for you,’ said Amarante.

‘No. It is not.’

‘I, on the other hand, only have a limited amount of time in which to improve.’

‘That need not necessarily be the case,’ he said calmly.

‘I am afraid I do not understand you.’

‘I can offer you all the time in the world, if you so wish it. I can also offer you knowledge beyond all human understanding and imagination.’

She stared at him for a few moments.

‘I have a rather fecund imagination,’ she said in the end.

‘Which is precisely the reason I am making you this offer… You need not come to a decision now. Take all the time you need and consider it. I shall return, and continue returning, until you have made your decision. If you decide against my offer, I shall leave and never trouble you again. …Oh, and I must not forget, this is a small gift from Atreus. He said to tell you that this is but a small sample of what we have to offer.’

He reached to his belt and unhooked a small, bronze scroll case and offered it to her. After a brief hesitation, Amarante accepted it, opened it, drew out the scroll it contained, and unfurled it. It took her only moments to recognise that she was looking at the missing part of the manuscript the German and she had translated just a few months earlier. Unable to entirely keep the surprise from her expression, she raised her eyes to him again.

‘Perhaps we could play another game when I return, even though I feel certain that the result will be much the same,’ he said, as he rose from his seat. ‘“Repetitio mater studiorum est”, as the Latins said, however. Is it not so?’

He strode to the door and was about to walk out into the corridor beyond, when she said, ‘How am I to consider your offer if I do not know what you are?’

He paused.

‘I am, what I am,’ he said. ‘I am a man.’

‘No man lives as long as you have, sir.’

‘…No human man, no. …You would call what I am “algul”,’ said Kyrus. And he was gone, vanishing out into the shadows beyond the door.

When he returned the following night, Amarante was waiting for him, sitting where she had been sitting the night before.

‘You are djinn,’ she said, asking a question in the manner of a statement.

Kyrus took the seat across from her.

‘In different lands, men would think of me as different things – none of them accurate. I am something that you would call “algul”.’

‘An algul is a djinnı.’

‘This is so. Hence, you might also call what I am “djinn”; though I am certainly not made of “smokeless fire”. My existence is, however, concealed – as the word djinn itself implies – so, for lack of a better one, I shall not contest the definition.’

‘You are not what I would have imagined an algul to be like.’

‘You would have imagined something… of a more monstrous or demonic appearance?’ he asked, crossing his legs and leaning back in his seat.

‘Perhaps. …I confess that I had never previously given the matter much thought.’

‘It is only natural. …Not all of us are the same, yet, to my knowledge, none of us appear perceptibly monstrous or demonic.’

‘I see…’ Amarante indicated the chessboard, set up anew in front of them. ‘Would you like the black or the white?’

‘You choose, madam.’

‘Very well, I shall take the black.’

He leaned forward and opened with his Queen’s pawn.

‘I have some questions,’ said Amarante as she made her own move.

‘I would certainly expect that you would. Please feel free to ask me anything you wish.’ He moved his Bishop’s pawn out to square four, to stand by the already advanced Queen’s pawn.

‘You feed on blood?’

‘Yes.’

Amarante moved her King’s pawn out to square three.

‘Human blood?’

‘Not exclusively. The blood of any warm-blooded animal can offer me sustenance; but human blood is preferable. I require less of it.’ Kyrus moved his King’s Knight out to Bishop’s three, to mirror Amarante’s first move.

‘It is more nourishing to you?’ she asked, as she advanced her Bishop’s pawn on the Queen’s side to square four.

‘Yes.’

He considered the board for a moment, then moved forward his Knight’s pawn on the King’s side by one square, to stand next to his already advanced Knight.

‘And do you kill, to feed?’

‘Not as a rule. No. I have no need to,’ he said, as Amarante captured his Queen’s pawn with her own Bishop’s pawn.

‘How is it, then, that you feed without men knowing? I expect there would be a great deal more talk of alguls if men knew…’

‘You are very right. There are several reasons why this is possible, some have to do with certain other abilities that we have, that each different one of us has, but, beyond this, it appears that we are equipped by nature to be able to feed in this manner. Our bite causes little or no pain… it is benumbing, and mildly intoxicating, to humans. Men that sleep will not wake, and men that are awake become disorientated and their wits addled, and soon forget, or it remains with them as the hazy memory of a dream. The wounds we cause are slight, hardly marked at all, the blood flow ceases almost immediately, and the wounds themselves heal rapidly.’

He captured Amarante’s belligerent pawn with his Knight.

‘I see…’ said Amarante, and moved her Queen’s pawn forward to stand directly in front of the white Knight. ‘And were you always what you are now? Were you born this way?’

‘No. I was once as human as you are, madam. …I was made what I am now.’

‘How?’

‘Atreus gave me of his blood to drink, a measure of it, each one of nine consecutive nights.’

As Amarante slowly raised her eyes from the board and silently stared at him, he moved his King’s Bishop to King’s Knight two. Then, feeling perhaps her eyes on him, he too looked up and met her gaze. She noticed for the first time how, despite the dimness of the room with but a single oil lamp burning, the black of his pupils remained contracted in the centre of the silvery sea of the grey iris, as though the room were brightly lit, or it were day outside. For a moment she did not speak, and neither did he. Then she returned her gaze to the board and moved her King’s pawn another step forward, to square four, to threaten his Knight.

‘I hazard that sunlight may be a problem for you,’ she said calmly.

‘To varying degrees, depending on the intensity. Light and heat… mostly light, are a problem, indeed,’ he agreed, as he withdrew his threatened Knight back to his Bishop’s column. ‘Yet not an insurmountable one. …Often, a cowled cloak is all that’s necessary.’

‘Not, I would suppose, at high noon, in high summer.’

‘No. Indeed. Then, I admit, a cowled cloak would not suffice to counter the problem,’ said Kyrus, as Amarante moved her King’s pawn yet another step forward to threaten his Knight yet again.

Kyrus returned his Knight to its previous, advanced position and once again out of danger, and Amarante captured his Bishop’s pawn with her Queen’s pawn.

‘Will you ever die?’ she asked, at length.

‘I do not know.’

Amarante, once again, raised her eyes and stared at him.

‘You do not know?’

‘Opinions on the matter differ, but no one truly knows whether our kind ever reaches an age where death comes naturally. A natural death, from old age, infirmity or disease has yet to be recorded, or observed, by reliable witnesses – or any witnesses, to my knowledge.’

Still Amarante stared at him, and in the end, she said, ‘Can you be killed?’

‘Of course,’ said Kyrus, leaning forward once more, to deploy his Queen’s Knight to Bishop’s square three. ‘I live, do I not? Hence, I may be killed, as all living things may be killed. Though the endeavour may require a little more effort than for most other living things. Our kind are very hardy. And we heal very rapidly. Yet, as with all living things, there are limits to what we are able to heal and recover from.’ He raised his eyes from the board, and found her still staring at him, considering him – and his words.

‘How old is the oldest of your kind that you know of?’ she asked at last.

‘The eldest of our kind count their age in millennia, not centuries, madam,’ he said.

Amarante searched his eyes for a moment longer then, slowly, blinked and turned back to the board. She moved her King’s Bishop forward to Queen’s Bishop four, and threatened Kyrus’s beleaguered Knight yet again. This time, he chose to ignore the threat, and he brought his Queen forward to Rook’s square four.

‘Check,’ he said.

Amarante moved her Bishop out to Queen’s two, and reversed the threat. If he wished to keep his Queen, he would needs move it. He did, and captured with it Amarante’s pawn on the same row. And now the black Bishop was in danger from the white Queen, and unprotected. Amarante moved out her own Queen for the first time, to Knight’s three, to support her Bishop.

Kyrus contemplated the board for a small while, and finally brought his Queen’s side Bishop out to King’s three, to support his Knight and hinder Amarante’s single most advanced pawn from moving even further forward.

‘Are there many of your kind of such a great age in the world?’ asked Amarante, once he had made his move.

‘No… Not many. Still, they are more than several…’

‘Have you met any of them?’

‘Yes. Some of them.’

Amarante deployed her second Knight, and brought it to stand by her Queen on Bishop’s three. Kyrus’s besieged Knight was once again under threat.

‘What are they like?’

He moved it out of danger, back to Bishop’s two.

‘Like all men – and women – each one, different from the other,’ he said, and watched her capture the white Queen’s Bishop with her black one. He considered the board, and pursed his lips, and accepted the exchange, for she had forced it on him. He captured with his Knight the offending, and menacing, black Bishop that had sneaked in behind the white lines. ‘I fear I am about to lose this game as well,’ he added.

Amarante moved her Queen’s Knight out to Rook’s four, looming threateningly over the white Queen, and waited. There was nowhere for the white Queen to flee to. It was trapped, in the middle of what seemed like a wide-open board, and would be taken no matter where it attempted to run. And once the Queen was gone, the white’s fate seemed inevitable.

Kyrus gently tipped the white King over and leaned back in his seat.

‘If, and when, you wish me to go,’ he said, ‘to give you time to think about what we have discussed, or to rest, you need but say so.’

Amarante was quietly studying him, head tilted slightly to one side, amber eyes calm and unflinching.

‘I have more questions,’ she said in the end.

That night, and the following one, and every night for two weeks, Amarante asked him questions, and he answered all of them with what she was convinced was utter candour. At no point did he show impatience, or indicate that she should be finally coming to a decision; nor that he was finding his nightly visits tiresome. When she realised that she was becoming so accustomed to his presence that she was beginning to forget what he was, she asked to be shown how he fed. Her demand, at first, appeared to unsettle him. But once she pointed out that if she were expected to decide whether she wished to be like him, for all eternity, that was something she needed to witness, he was forced to concede that her demand was reasonable. He promised that he would show her the following night.

The next day, Amarante left her house, in the middle of the night, for the first time in her life; and she watched the German feed on a man’s blood. She was shaken, not by what she saw, but by the fact that she saw him in his true light for the first time, and rather than horror, she felt nothing. She had reacted to what she had seen in much the same way as she had had in the past, when watching a cat catch a mouse. It was the natural way of things; it was what the cat did, what it was built to do. Nature, or God, had created it in this way. Besides, the creature she had just watched, unlike the cat, had been swift and clean in his hunt, and had not killed or toyed with, or tortured. He had caught his prey, fed, and released his prey once more; a dazed, confused prey, but a live one nonetheless. Amarante made her decision that very night.

Once they had returned to her house, and were once again standing in the reception room, she turned to him and simply said, ‘I accept your offer.’

Kyrus seemed surprised. Perhaps he had expected that what she had witnessed would have caused her to recoil from the notion – and from him.

‘Are you certain?’ he said at length.

‘I am.’

‘Then, I shall return tomorrow and, if your answer is still the same, there will be many more things, of a practical nature, to discuss and consider.’

‘My answer will be the same,’ said Amarante simply.

‘I have little doubt. And, for my part, hope that it will. Nonetheless… I wish to hear it from you again, tomorrow.’

Amarante did not change her mind, and the answer Kyrus received the following night was the same. He was pleased. Despite the gravity of his manner and his reserved nature, Amarante was beginning to be able to tell.

For Amarante to merely disappear from Toledo was possible, but, for more than several reasons, undesirable. For one matter, there was her library to consider. And then there was the rest of her estate. And, of course, a mysterious disappearance was bound to excite questions, talk, and curiosity – all of which it was preferable to avoid. Nor could she remain in Toledo, a city where so many knew her, and of her family.

Had she been a man, matters would have been simpler.

As it was, there was but one excuse, short of pretending to retire to the cloister, that would legitimately explain her departure from the city, and also allow her to retain her wealth.

‘You shall have to wed,’ said Kyrus. ‘…Or, rather, we shall have to make all the arrangements as if you were about to.’

‘Whom am I marrying?’

‘Me.’

‘You?’ said Amarante, with a raise of an eyebrow.

‘I’m afraid I shall have to do,’ said Kyrus evenly, and with perhaps a hint of self-deprecation.

‘You misunderstand me. I but meant that my acquaintances will expect to meet the proposed husband, and in this case, this would be you.’

‘It is no matter. Your household already knows me. This is a good start. It will all seem less sudden. Besides, you hold the widow’s privilege of being able to make your own choice this time, and since you have no other living family, you have no need to concern yourself about any possible objections. …Since you hold significant property, however, it would perhaps be wise to also obtain approval from… higher-up. You may leave that to me – along with all other practicalities. I shall draw out the marriage contract, and any other charters necessary once we have decided how we shall be managing your property. I suggest you lease it to the Church. For the long term, it is the most prudent and secure choice…’

‘If the Church is interested, or may be convinced, to rent these properties…’

‘So long as the sum we ask for is reasonably modest, I do not foresee any problems. As I said, leave these considerations to me. What you need concern yourself with are your acquaintances, advising them of the news, choosing those you wish to witness the signing of the marriage contract, and other such formalities. In these matters, I shall let myself be guided by you, for you know best what each one wishes, and expects, to hear and see.’

‘They shall certainly expect to see you.’

‘Naturally.’

‘At a more reasonable time of day than the one you usually reserve for your visits.’

‘I am aware of that.’

‘Will this be a problem?’

‘No.’

‘They will also expect to see a wedding.’

‘The wedding will take place in your new home, in Mainz.’

‘That will likely raise some eyebrows, and questions. And talk,’ said Amarante.

‘They will accept it.’

‘Are you certain?’

‘Yes.’

‘In the same way that the Church will agree to lease my properties?’ suggested Amarante, after a moment.

Kyrus glanced at her and, for once, a trace of amusement gleamed briefly in his eyes. ‘Yes,’ he said.

‘I see. …Very well. Then, you shall have to begin visiting. We should begin by reminding my household of your existence.’

‘As you wish.’

‘In a few days, a week perhaps, I shall tell Jasmín that you have proposed marriage. From her, I have no doubt, everyone else will very quickly become acquainted with the news. Then, I would be greatly surprised if they do not come to me, in pursuit of further details. Once this happens, we will arrange to introduce you. We shall let pass another week, and then I shall let certain of them know that I have accepted your proposal, and ask of them that they witness the signing of the contract,’ Amarante concluded.

Kyrus nodded.

‘Very well. I can see nothing at fault with this strategy. …Save that I fear it will be an uncommonly wet and overcast June,’ he added. ‘…But it cannot be helped.’

It did indeed rain. Frequently. Clouds would begin slowly gathering in the early afternoon and would dim the brilliant sunshine, and they would pile up on top of each other, disinclined, it seemed, to move on, and grow heavier, and the air would become oppressive with their load. They would hang there, suspended and ponderous, for hours, until at last, in the late afternoon, or early evening, their burden would become too heavy even for themselves, and the rain would come. In large, fat drops at first, as though the sky were bleeding – and these would become a stream, and, at last, short-lived but torrential downpours. Afterwards, as the clouds would slowly dissipate in a periwinkle sky, the setting sun gave them glowing colours of orange and rose, in a twilight so radiantly clear, the air might have been washed clean with the rain.

Hardly a day went by without a dreary, cloudy hour or two, even if the rain held off in the end and the clouds harmlessly dissipated.

Kyrus came to Amarante’s house either early in the afternoon, once the clouds had begun gathering, and had left again before the rain arrived, or he arrived later in the day, and departed again in the turquoise and pink light of sunset. Not once, during his visits, was the day clear – though it may well have been earlier, and was certainly so again later in the evening.

Once, he came with a manservant, Hubert, a lean, wiry man, quiet, and with dark, keen eyes. Of an age with Kyrus, he seemed. Jasmín recognised in him the man that had, but a few weeks earlier, handed her a small, cloth-wrapped package for her mistress. Though Amarante had not spoken a word about its contents, Jasmín, when handling it, had recognised what lay beneath the wrapping for what it was, a book. Neither had the coincidence gone unnoticed to her that Amarante had, that same day, visited an old friend of her father’s to ask him about a book she had recently acquired. A book, Jasmín knew, was a precious thing; as valuable as any finery or jewellery of gold, or silver, and gems – and would certainly be more treasured by her mistress than any such thing. And now, the man that had sent this costly gift was visiting. And this time, he was not spending his time in the library, or working, but in conversation with her mistress, or playing chess.

Inevitably, Jasmín drew certain conclusions from this concurrence of events. When Amarante confirmed her suspicions and spoke to her of marriage, Jasmín gasped. She clasped her hands to her chest. And then she cried. Almost incoherent with joy, despite the changes in her own life something such as this would mean, she praised God for the wonderful news and exclaimed that, though far be it from her to speak ill of the dead, and what’s more of a dear, kind man like Amarante’s late husband, anyone could see that this was a much better match, a man still young, in his prime, and she wished her many, long years of happiness, and many children. And wasn’t he so handsome? Blond, like an angel. Their children would be blond like angels too, Jasmín decided. And, still tearful and sniffling, she scurried off.

As expected, soon afterwards, Amarante’s acquaintances began remembering they had reason to visit – or, rather transparently, invented one.

When the time came for them to meet the proposed husband, all appeared immediately and entirely enchanted by him. His words, on any matter, were accepted with surprising alacrity, and none displayed the least tendency to question or contradict him, even on matters Amarante would have thought inevitable. Kyrus spoke well, it was true, and responded with reason and ease to all discussion and questions. Yet, there was also something different about him. Something all but indefinable, yet still noticeable, to Amarante, who knew him better and for some little while now. It was surely new. There was something noble and imposing in his bearing, though his manner had not changed – something little different from majesty. A man would as lief have challenged the pronouncements of a just and noble king, as he would have Kyrus’s words those days.

And yet, when he was alone with her, he was as she had always known him to be, and no different. Only in the presence of others did this striking transformation ever take place.

The marriage contract, when the time came for it to be produced, was a document worthy of marvel, not only for the flawlessness of its composition, but also for the sign and seal of the archdeacon of Toledo as the first witness that it bore, and which Kyrus had somehow succeeded in securing. Three more witnesses added their signs to the charter, and the matter was closed. Amarante would marry, and the wedding would take place in her new home, in Mainz.

Preparations for her departure started, several more charters were produced, all in Kyrus’s hand, the hand she knew now so well, and her properties were leased to the Church. Only the contents of the house, the furniture and furnishings all, save but a few small things, Amarante gifted to her servants that she had known all or most of her life, for where she was going, they could not follow. It was a large gift, a small fortune in itself, which she divided equally between them. Only Jasmín received a portion by a measure larger than the rest, for Amarante had known her all her life, and she was no longer young, and still unmarried and this, perhaps, would help her build a new life; marry even. It was certainly enough.

Jasmín cried again.

Ten days before leaving the city she had spent her entire life in, Amarante tasted Kyrus’s blood for the first time.

It was dense, and dark, and sweet like the best of sweetest wines; its scent heady, and the metallic aftertaste so vibrant, it scintillated like silver in the sun.

Each night, for nine consecutive nights, Amarante drank of Kyrus’s blood. And as the days went by, she began to change. Less and less she felt fatigue and the need to sleep, and when she did, it was in the afternoon that she did so. The rapidly rising seasonal heat troubled her more than usual, and so did the brightness of the day. It was indeed warm, and the only means of combating the heat was to keep the shutters drawn to, so that is what she did, and this seemed only natural to her household, who thought nothing more of it. The occasional twinge of pain she felt deep within the root of her canines for a few days was less than severe, and by the end disappeared entirely.

It was several days before she noted that her heartbeat had begun slowing, and so had her breathing. Both slowed rapidly even further until, by the end, she needed sit quietly with her attention trained on her body to be able to even mark the occurrence of either. While she did not exert herself in any way, it seemed that her heart would beat but two or three times every minute – and neither did she draw breath more often. Unless she spoke; then, clearly, breath was necessary and came naturally. She could not herself feel it, but she supposed that now her skin would feel cool to the touch, despite the heat, like Kyrus’s did and she had marked long since. In the end, Jasmín showed concern because she judged that Amarante looked a little pale, and Amarante was forced to take great pains to assuage all her many and various concerns.

The last night, Kyrus drew back his sleeve and bared his forearm.

‘This time, you take,’ he said. ‘For you will always take, from now on.’

Until that night, he had always offered his blood to her in a cup. He would cut his wrist open with a small dagger and let his blood flow into it and, even as she watched, Amarante would see the cut knit together and heal, with no mark left behind to show for it.

‘None will willingly offer you of their life – none but those closest to you. From now on, you take,’ he said again.

For a moment, Amarante hesitated. Then she took Kyrus’s arm and brought his wrist to her lips.

What others are saying:

“A heavily detailed historical background with a fresh, deeply literary view of immortals. … Incredibly dense and colorful.”

— Publishers Weekly

“Those who are of a more historical novel bent, fans of vampiric fiction, or both, are in for a rare treat in Bad Bishop.”

— Abyss & Apex

“An engrossing read, with settings and descriptions which feel historically accurate, despite the vampire protagonists.”

— Helion

“If you are a chess player there is another layer of subtlety that adds to but is not essential to understanding of the plot. What matters is the beautiful writing, the extremely well-crafted story, and Irene Soldatos’ profound knowledge of the historical epoch she is writing about. Bad Bishop is unlike any historical novel I have read before.”

— Jane Dougherty

“Bad Bishop is a book that will demand your full attention. … The mysteries, captivating characters, and well thought-through intrigue hold up to close scrutiny and it is obvious that a lot of dedication and meticulous research has gone into the writing of this book. Although the main characters are immortals, this is not a book with sparkly vampires — this is fantasy combined with history and mystery!”

— K. Schönon