A marble bust of Caligula restored to its original colours. The colours were identified from particles trapped in the marble. (Photo by Marsyas)

Caligula had only a single taste of warfare, and even that was unpremeditated. At Bevagna, where he went to visit the river Clitumnus and its sacred grove, someone reminded him that he needed Batavian recruits for his bodyguard; which suggested the idea of a German expedition. He wasted no time in summoning regular legions and auxiliaries from all directions, levied troops with the utmost strictness, and collected military supplies on an unprecedented scale. Then he marched off with such rapidity that the Guards battalions could not keep up with him except by breaking tradition: they had to tie their standards on the pack-mules. Yet, later, he became so lazy and self-indulgent that he travelled in a litter borne by eight bearers; and, whenever he approached a town, made the inhabitants sweep the roads and lay the dust with sprinklers.

After reaching his headquarters, Caligula showed how keen and severe a commander-in-chief he intended to be by ignominiously dismissing any general who was late in bringing along the auxiliaries he required. Then, when he reviewed the legions, he discharged several veteran leading-centurions on grounds of age and incapacity, though some had only a few more days of their service to run; and, calling the remainder a pack of greedy fellows, scaled down their retirement bonus to sixty gold pieces each.

All that he accomplished in this expedition was to receive the surrender of Adminius, son of the British King Cymbeline, who had been banished by his father and come over to the Romans with a few followers. Caligula, nevertheless, wrote an extravagant despatch, which might have persuaded any reader that the whole island had surrendered to him, and ordered the couriers not to dismount from their post-chaise on reaching the outskirts of Rome – although wheeled traffic was forbidden in the streets during daylight hours – but make straight for the Forum and the Senate House, and take his letter to the Temple of Mars for personal delivery to the Consuls, in the presence of the entire Senate.

Since the chance of military action appeared very remote, he presently sent a few of his German bodyguard across the Rhine, with orders to hide among the trees. After luncheon scouts hurried in to tell him excitedly that the enemy were upon him. He at once galloped out, at the head of his staff and a few Guards cavalry, to halt in the nearest thicket, where they chopped branches from the trees and dressed them like trophies; then, riding back by torchlight, he taunted as cowards all who had failed to follow him, and awarded his fellow-heroes a novel fashion in crowns – he called it ‘The Ranger’s Crown’ — ornamented with sun, moon, and stars. On another day he took some German hostages from a military school, where they were being taught the rudiments of Latin, and secretly ordered them on ahead of him. Later, he left his dinner in a hurry and took his cavalry in pursuit of them, as though they had been fugitives. He was no less melodramatic about this foray: when he returned to the hall after catching the hostages and bringing them back in irons, and his officers reported that the army was marshalled, he made them recline at table, still in their corselets, and quoted Virgil’s famous advice: ‘Be steadfast, comrades, and preserve yourselves for happier occasions!’ He also severely reprimanded the absent Senate and People for enjoying banquets and festivities, and for hanging about the theatres or their luxurious country-houses while the Emperor was exposed to all the hazards of war.

In the end, he drew up his army in battle array facing the Channel and moved the siege-engines into position as though he intended to bring the campaign to a close. No one had the least notion what was in his mind when, suddenly, he gave the order: ‘Gather sea-shells!’

He referred to the shells as ‘plunder from the sea, due to the Capitol and to the Palace’, and made the troops fill their helmets and tunic-laps with them; commemorating this victory by the erection of a tall lighthouse, not unlike the one at Pharos, in which fires were to be kept going all night as a guide to ships. Then he promised every soldier a bounty of four gold pieces, and told them: ‘Go rich, go happy!’ as though he had been excessively generous.

He now concentrated his attention on the imminent triumph. To supplement the few prisoners taken in frontier skirmishes and the deserters who had come over from the barbarians, he picked the tallest Gauls of the province – ‘those worthy of a triumph’ – and some of their chiefs as well, for his supposed train of captives. These had not only to grow their hair and dye it red, but also to learn German and adopt German names. The triremes used in the Channel were carted overland most of the way; and he sent a letter ahead instructing his agents to prepare a triumph more lavish than any hitherto known, but at the least possible expense to the Privy Purse; and added that everyone’s property was at their disposal.

Before leaving Gaul he planned, in a sudden access of cruelty, to massacre the legionaries who, at news of Augustus’s death, had mutinously besieged his father Germanicus’s headquarters; he had been there himself as a little child. His friends barely restrained him from carrying this plan out, and he could not be dissuaded from ordering the execution of every tenth man; for which purpose they had to parade without swords or javelins, and surrounded by armed horsemen. But when he noticed that a number of legionaries, scenting trouble, were slipping away to fetch their weapons, he hurriedly absconded and headed straight for Rome.1

1 Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, trans. Robert Graves, London: The Folio Society, 1964, pp. 172-174.

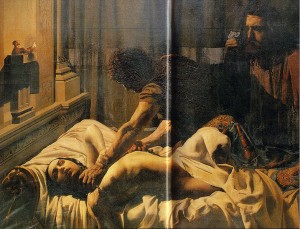

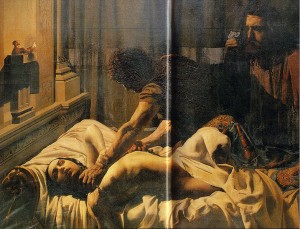

When Chilperic1 saw this [the marriage of Sigebert2 to the Visigoth princess Brunhild3], although he had already too many wives, he asked for her sister Galswinth, promising through his ambassadors that he would put aside the others if he could only obtain a wife worthy of himself and the daughter of a king. Her father accepted these promises and sent his daughter with much wealth, as he had done before. Now Galswinth was older than Brunhild. And coming to king Chilperic she was received with great honour, and united to him in marriage, and she was also greatly loved by him. For she had brought great treasures. But because of his love of Fredegund whom he had had before, there arose a great scandal which divided them. Galswinth had already been converted to the catholic law and baptised. And complaining to the king that she was continually enduring outrages and had no honour with him, she asked to leave the treasures which she had brought with her and be permitted to go free to her native land. But he made ingenious pretences and calmed her with gentle words. At length he ordered her to be strangled by a slave and found her dead on the bed. After her death God caused a great miracle to appear. For the lighted lamp which hung by a rope in front of her tomb broke the rope without being touched by anyone and dashed on the pavement, and the hard pavement yielded under it and it went down as if into some soft substance and was buried to the middle but not at all damaged. Which seemed a great miracle to all who saw it. But when the king had mourned her death a few days, he married Fredegund again. After this action his brothers thought that the aforementioned queen had been killed at his command, and they expelled him from the kingdom. Chilperic at that time had three sons by his former wife Audovera, namely Theodobert, whom we have mentioned above, Merovech and Clovis.

When Chilperic1 saw this [the marriage of Sigebert2 to the Visigoth princess Brunhild3], although he had already too many wives, he asked for her sister Galswinth, promising through his ambassadors that he would put aside the others if he could only obtain a wife worthy of himself and the daughter of a king. Her father accepted these promises and sent his daughter with much wealth, as he had done before. Now Galswinth was older than Brunhild. And coming to king Chilperic she was received with great honour, and united to him in marriage, and she was also greatly loved by him. For she had brought great treasures. But because of his love of Fredegund whom he had had before, there arose a great scandal which divided them. Galswinth had already been converted to the catholic law and baptised. And complaining to the king that she was continually enduring outrages and had no honour with him, she asked to leave the treasures which she had brought with her and be permitted to go free to her native land. But he made ingenious pretences and calmed her with gentle words. At length he ordered her to be strangled by a slave and found her dead on the bed. After her death God caused a great miracle to appear. For the lighted lamp which hung by a rope in front of her tomb broke the rope without being touched by anyone and dashed on the pavement, and the hard pavement yielded under it and it went down as if into some soft substance and was buried to the middle but not at all damaged. Which seemed a great miracle to all who saw it. But when the king had mourned her death a few days, he married Fredegund again. After this action his brothers thought that the aforementioned queen had been killed at his command, and they expelled him from the kingdom. Chilperic at that time had three sons by his former wife Audovera, namely Theodobert, whom we have mentioned above, Merovech and Clovis.

Gregory of Tours History of the Franks, 4. 28

Translation based on Earnest Brehaut [1916]

1 c. 539 – September 584, King of Neustria

2 c. 535 – c. 575, King of Austrasia (half-brother of Chilperic)

3 c. 540–568, daughter of the Visigoth King Athanagild

The king [Chlothar]1 had seven sons by several wives; namely, by Ingund, Gunthar, Childeric, Charibert, Gunthram, Sigibert, and a daughter Chlodoswintha; by Aregund, sister of Ingund, Chilperic; and by Chunsina he had Chramn. I will tell you why it was he married his wife’s sister. While he was married to Ingund and loved her alone, he received a suggestion from her saying: “My lord has done with his slave-girl what he pleased and has admitted me to his bed. Now let my lord the king hear what his handmaiden would suggest to make his favour complete. I beg that you consent to find a husband for my sister, your servant, a man of dignity and wealth, so that I shall not be humiliated but rather exalted and shall be able to serve you more faithfully.” As soon as he heard this, because he was licentious beyond all measure, he began to love Aregund and went to the estate on which she was living and married her himself. Having done this he returned to Ingund and said: “I have accomplished the favour which your sweet self asked of me. I looked for a man of riches and wisdom to unite to your sister. I found no one better than myself. And so allow me to tell you that I have married her, which I think will not displease you.” And she replied; “Let my Lord do what seems good in his eyes; only let his handmaid live in favour with the king.”

Gregory of Tours, History of the Franks, 4. 3

Translation based on Earnest Brehaut [1916]

1 c. 497 – 29 November 561, King of the Franks

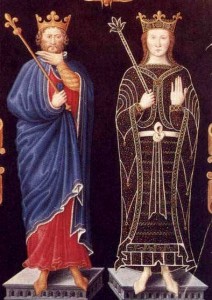

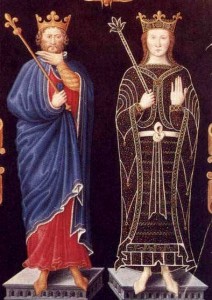

Chilperic I and Fredegund

Rigunth1, daughter of Chilperic2, often made malicious charges against her mother [Fredegund]3 and said that she was the mistress and that her mother should pay her homage, and she continuously attacked her with abuse and provocation. Sometimes they would strike each other with slaps and punches. Her mother said to her: “Why are you so troublesome to me, daughter? Look, here are your father’s things that I have. Take and do with them as you like.” And she went into the treasury and opened a chest quite full of necklaces and costly jewels. For a long time she took them out one by one and handed them to her daughter but finally said: “I am tired; you put in your hand and take what you find.” And when she thrust in her arm and was taking things from the chest, her mother seized the lid and slammed it down on her neck. And she was holding it down with such force that the lower board was crushing her daughter’s gullet so that her eyes were actually ready to pop out when one of the maids who was within called loudly: “Run, I beg you, run; my mistress is being choked to death by her mother.” And those who were awaiting their coming outside rushed into the little room and saved the girl from imminent death and led her out. After that their hostility became even more vehement and they were always brawling and hitting each other, above all because of Rigunth’s constant sleeping around.

Gregory of Tours, History of the Franks 9. 34

Translation based on Earnest Brehaut [1916]

1 c. 570 – after 585.

2 Chilperic I (c. 539 – September 584), king of Neustria.

3 Concubine and then wife of Chilperic (d. 597)

8. ext. 13. On the other hand, Drypetine, the daughter of King Mithridates and Queen Laodice, looked very ugly because of her double row of teeth.2 She joined her father in exile when he was defeated by Pompey.3

8. ext. 14. A man had eyes that were quite amazing. It is a definite fact that he had very sharp eyesight and that he could even see the Carthaginian ships setting sail if he looked out from the harbour of Lilybaeum.4

8. ext. 15. The heart of Aristomenes of Messenia was even more amazing than the eyes of that man.5 Aristomenes had often been captured and then escaped through trickery, but the Athenians finally got him. Intrigued by his exceptional intelligence, they cut open his heart, and discovered that it was full of hairs.6

8. ext. 16. The poet Antipater of Sidon caught a fever every year on one day only – his birthday.7 When he reached the end of his days, he was finished off on his birthday by this illness, which attacked him at its usual time.

8. ext. 17. It is a good place to tell the story of the philosophers, Polystratus and Hippoclides.8 They were born on the same day, followed the same philosophical school founded by Epicurus,9 shared the fortunes they had inherited, set up a school together, and when they had reached a ripe old age, died at the same time. Who could avoid thinking that this great equal partnership in fortune and in friendship was produced, nourished, and brought to completion in the bosom of the goddess Concord herself?

Valerius Maximus, Memorable Deeds and Sayings; One Thousand Tales from Ancient Rome, trans. Henry John Walker, Hackett Publishing: 2004, p. 41.

1Prusias Monodous (“one-toothed”) was the son of Prusias II (king of Bithynia from 181-149 B.C.E.).

2Mithridates VI was king of Pontus from 120 to 63 B.C.E.

3Mithridates VI was defeated by Pompey in 66 B.C.E. and had to flee from his kingdom. Drypetine died on the journey.

4Lilybaeum was on the west coast of Sicily and over 100 miles from Carthage in north Africa.

5Aristomenes was the hero of the Messenian rebellion against Sparta in the first half of the seventh century B.C.E.

6Aristomenes was captured and killed by the Spartans, not the Athenians.

7Antipater of Sidon (in Phoenicia) wrote Greek epigrams in the second century B.C.E.

8Polystratus was an Epicurean philospher of the third century B.C.E. He was the third head of the Epicurean School.

9Epicurus founded his philosophical school in Athens in 306 B.C.E.