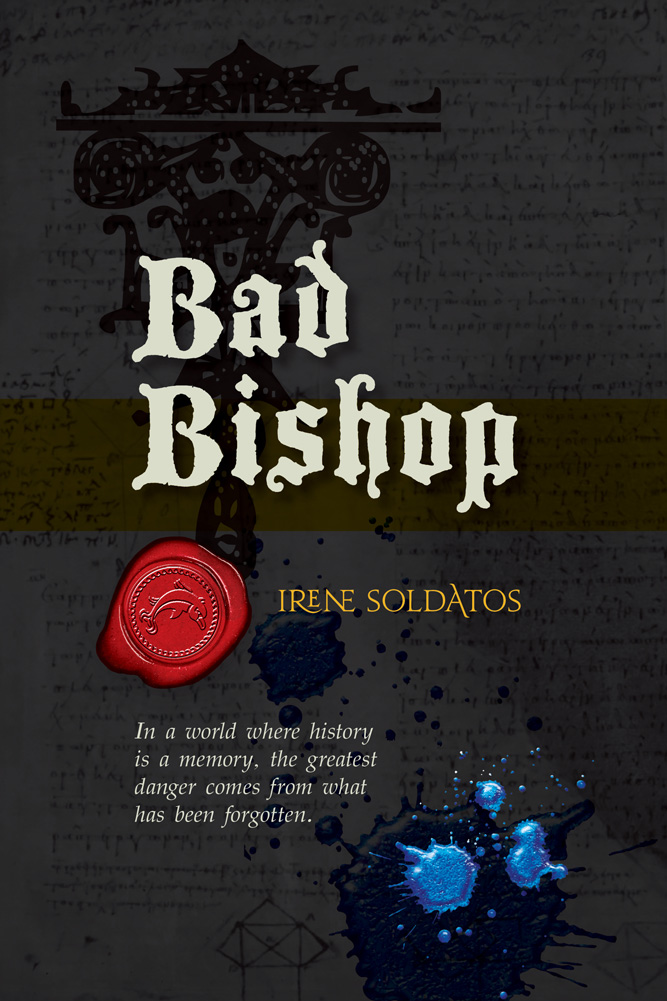

Part 3, following on from part 1 and part 2.

Chapter XV.—Of Hypatia the Female Philosopher.

Chapter XV.—Of Hypatia the Female Philosopher.

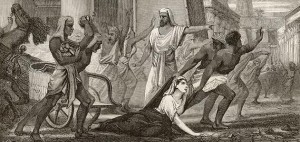

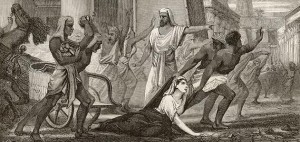

There was a woman at Alexandria named Hypatia, daughter of the philosopher1 Theon, who made such attainments in literature and science, as to far surpass all the philosophers of her own time. Having succeeded to the school of Plato and Plotinus, she explained the principles of philosophy to her auditors, many of whom came from a distance to receive her instructions. On account of the self-possession and ease of manner, which she had acquired in consequence of the cultivation of her mind, she not unfrequently appeared in public in presence of the magistrates. Neither did she feel abashed in coming to an assembly of men. For all men on account of her extraordinary dignity and virtue admired her the more. Yet even she fell a victim to the political jealousy which at that time prevailed. For as she had frequent interviews with Orestes, it was calumniously reported among the Christian populace, that it was she who prevented Orestes from being reconciled to the bishop. Some of them therefore, hurried away by a fierce and bigoted zeal, whose ringleader was a reader named Peter, waylaid her returning home, and dragging her from her carriage, they took her to the church called Cæsareum, where they completely stripped her, and then murdered her with tiles2.After tearing her body in pieces, they took her mangled limbs to a place called Cinaron, and there burnt them. This affair brought not the least opprobrium, not only upon Cyril,but also upon the whole Alexandrian church. And surely nothing can be farther from the spirit of Christianity than the allowance of massacres, fights, and transactions of that sort. This happened in the month of March during Lent, in the fourth year of Cyril’s episcopate, under the tenth consulate of Honorius, and the sixth of Theodosius.3

1 and mathematician. He arranged Euclid’s Elements and Ptolemy’s Handy Tables.

2 Tile shards, presumably, i.e. flayed her alive with something like this.

3 Socrates and Sozomenus, Ecclesiastical Histories, ed. and trans. Philip Schaff, WM. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Michigan, p. 160

Part 2 of series of events, which began here.

Theophilus Bishop of Alexandria with the Serapeum he destroyed

1 The previous Bishop of Alexandria, who caused the Serapeum, along with other pagan temples, to be destroyed.

2 Socrates and Sozomenus, Ecclesiastical Histories, ed. and trans. Philip Schaff, WM. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Michigan, p. 160

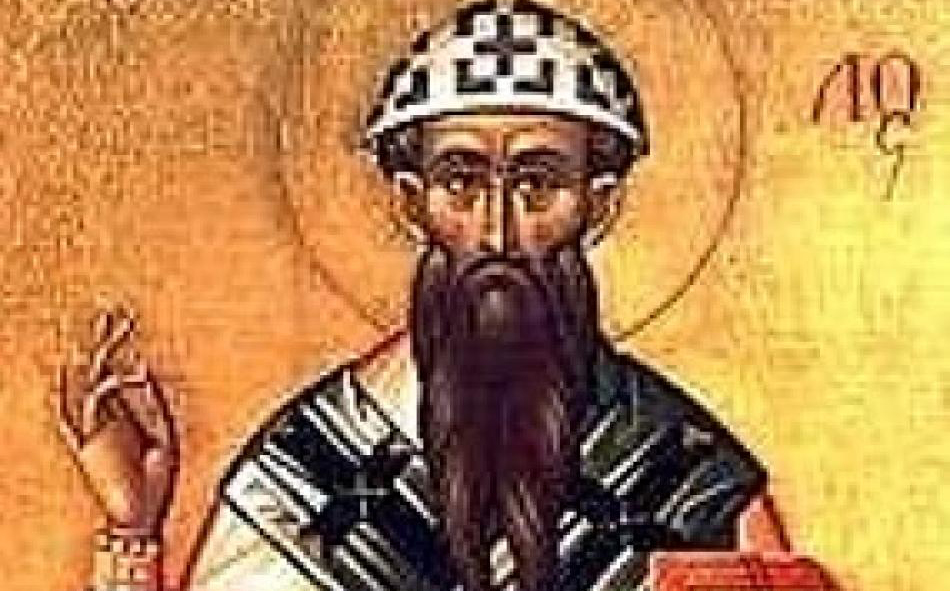

Bishop Cyril of Alexandria

This is the first of three posts all of which deal with one series of events. The series of events leading to the murder of the pagan philosopher and scientist Hypatia by a Christian mob in Alexandria in 425 C.E. She was, however, but collateral damage in a much more important struggle; that of secular versus religious authority. Nevertheless, her death sealed the victory of religious authority, since after this the Prefect, Orestes, gives up his struggle against Bishop Cyril, he gradually fades from political life, and finally disappears from historical record altogether. Where he went, what he did in later life, where, when and how he died, we don’t know.

The text is from the Christian historiographer Socrates Scholasticus’s Historia Ecclesiastica. He was born in Constantinople c. 380 C.E. and died some time after 439. The full text of Historia Ecclesiastica in English translation can be found here.

Chapter XIII.—Conflict between the Christians and Jews at Alexandria: and breach between the Bishop Cyril and the Prefect Orestes.

About this same time it happened that the Jewish inhabitants were driven out of Alexandria by Cyril the bishop on the following account. The Alexandrian public is more delighted with tumult than any other people: and if at any time it should find a pretext, breaks forth into the most intolerable excesses; for it never ceases from its turbulence without bloodshed. It happened on the present occasion that a disturbance arose among the populace, not from a cause of any serious importance, but out of an evil that has become very popular in almost all cities, viz. a fondness for dancing exhibitions.

In consequence of the Jews being disengaged from business on the Sabbath, and spending their time, not in hearing the Law, but in theatrical amusements, dancers usually collect great crowds on that day, and disorder is almost invariably produced. And although this was in some degree controlled by the governor of Alexandria, nevertheless the Jews continued opposing these measures. And although they are always hostile toward the Christians they were roused to still greater opposition against them on account of the dancers. When therefore Orestes the prefect was publishing an edict—for so they are accustomed to call public notices—in the theatre for the regulation of the shows, some of the bishop Cyril’s party were present to learn the nature of the orders about to be issued. There was among them a certain Hierax, a teacher of the rudimental branches of literature, and one who was a very enthusiastic listener of the bishop Cyril’s sermons, and made himself conspicuous by his forwardness in applauding.

When the Jews observed this person in the theatre, they immediately cried out that he had come there for no other purpose than to excite sedition among the people. Now Orestes had long regarded with jealousy the growing power of the bishops, because they encroached on the jurisdiction of the authorities appointed by the emperor, especially as Cyril wished to set spies over his proceedings; he therefore ordered Hierax to be seized, and publicly subjected him to the torture in the theatre.

Cyril, on being informed of this, sent for the principal Jews, and threatened them with the utmost severities unless they desisted from their molestation of the Christians. The Jewish populace on hearing these menaces, instead of suppressing their violence, only became more furious, and were led to form conspiracies for the destruction of the Christians; one of these was of so desperate a character as to cause their entire expulsion from Alexandria; this I shall now describe. Having agreed that each one of them should wear a ring on his finger made of the bark of a palm branch, for the sake of mutual recognition, they determined to make a nightly attack on the Christians.

They therefore sent persons into the streets to raise an outcry that the church named after Alexander was on fire. Thus many Christians on hearing this ran out, some from one direction and some from another, in great anxiety to save their church. The Jews immediately fell upon and slew them; readily distinguishing each other by their rings.

At daybreak the authors of this atrocity could not be concealed: and Cyril, accompanied by an immense crowd of people, going to their synagogues—for so they call their house of prayer—took them away from them, and drove the Jews out of the city, permitting the multitude to plunder their goods. Thus the Jews who had inhabited the city from the time of Alexander the Macedonian were expelled from it, stripped of all they possessed, and dispersed some in one direction and some in another. One of them, a physician named Adamantius, fled to Atticus bishop of Constantinople, and professing Christianity, some time afterwards returned to Alexandria and fixed his residence there.

But Orestes the governor of Alexandria was filled with great indignation at these transactions, and was excessively grieved that a city of such magnitude should have been suddenly bereft of so large a portion of its population; he therefore at once communicated the whole affair to the emperor. Cyril also wrote to him, describing the outrageous conduct of the Jews; and in the meanwhile sent persons to Orestes who should mediate concerning a reconciliation: for this the people had urged him to do. And when Orestes refused to listen to friendly advances, Cyril extended toward him the book of gospels,believing that respect for religion would induce him to lay aside his resentment. When, however, even this had no pacific effect on the prefect, but he persisted in implacable hostility against the bishop, the following event afterwards occurred.1

1Socrates and Sozomenus, Ecclesiastical Histories, ed. and trans. Philip Schaff, WM. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Michigan, p. 159-160

Chapter XV.—Of Hypatia the Female Philosopher.

Chapter XV.—Of Hypatia the Female Philosopher.