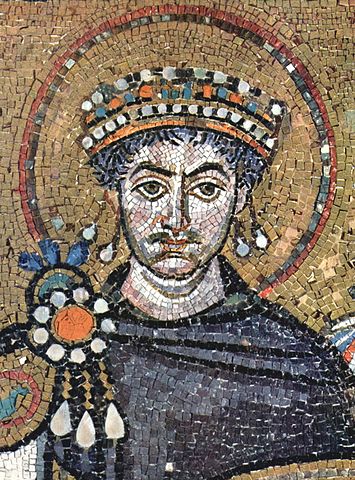

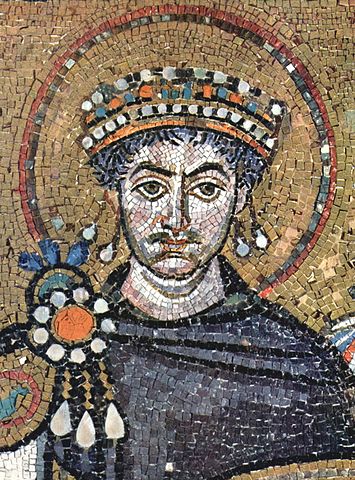

Let us stay in the 6th century for a bit, but this time move to the East. Justinian I (c. 482 C.E. – 14 November 565 C.E.), known as The Great – which I deliberately place in inverted commas – was Byzantine Emperor from 527-565 C.E. He is considered a saint by the Easter Orthodox Church. He famously married his mistress Theodora, a professional courtesan, who became extraordinarily influential in the politics of the Empire. Justinian sought to revive the Empire’s greatness by reconquering the lost western half of the Roman Empire. He oversaw the uniform rewriting of Roman Law, the Corpus Juris Civilis, which is still the basis of civil law in many modern states. Unfortunately he also wrote many laws, and changed earlier ones; for example forbidding women from getting divorced except under very specific circumstances, whereas previously, because marriage relied on the concept of consent, women could divorce by simply not wishing to be married any more. All they needed do was send a note to their husbands informing them of the fact. Without consent, there was no marriage under earlier Roman Law. Now, a woman could divorce her husband only if one of the following reasons applied:

Let us stay in the 6th century for a bit, but this time move to the East. Justinian I (c. 482 C.E. – 14 November 565 C.E.), known as The Great – which I deliberately place in inverted commas – was Byzantine Emperor from 527-565 C.E. He is considered a saint by the Easter Orthodox Church. He famously married his mistress Theodora, a professional courtesan, who became extraordinarily influential in the politics of the Empire. Justinian sought to revive the Empire’s greatness by reconquering the lost western half of the Roman Empire. He oversaw the uniform rewriting of Roman Law, the Corpus Juris Civilis, which is still the basis of civil law in many modern states. Unfortunately he also wrote many laws, and changed earlier ones; for example forbidding women from getting divorced except under very specific circumstances, whereas previously, because marriage relied on the concept of consent, women could divorce by simply not wishing to be married any more. All they needed do was send a note to their husbands informing them of the fact. Without consent, there was no marriage under earlier Roman Law. Now, a woman could divorce her husband only if one of the following reasons applied:

- He was implicated in a plot against the government or he knew of one and did nothing about it. (Treason)

- He has attempted to kill her or did not warn her of an attempt by others.

- He seeks to deliver her to another man for the purpose of committing adultery.

- He accuses her of adultery but fails to prove his case.

- He entertained another woman in his wife’s home or he is frequently with another woman and refuses to stop after having been warned by his wife’s kinsman or “other person worthy of confidence.”

Not quite the same thing.

Also, Justinian closed Plato’s Academy in Athens, and introduced two new statutes which decreed the total destruction of paganism, even in private life. Below is the description of what these led to, by the historian Procopius.

Procopius of Caesarea (500 C.E. – c. 565 C.E.) was a contemporary of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. He is considered the last major historian of the ancient world. He wrote the Wars of Justinian, the Buildings of Justinian and the celebrated Secret History, from which the following excerpt is taken.

And many straight away went everywhere from place to place and compelled such persons as they met to change from their ancestral faith.1 And since such action seemed unholy to the farmer class, they all resolved to make a stand against those who brought this message. So, then, while many were being destroyed by the soldiers and many even made away with themselves, thinking in their folly that they were doing a most righteous thing, and while the majority of them, leaving their homelands, went into exile, the Montani, whose home was in Phrygia, shutting themselves up in their own sanctuaries, immediately set their churches on fire, so that they were destroyed together with the buildings in senseless fashion, and consequently the whole Roman Empire was filled with murder and with exiled men.

And when a similar law was immediately passed touching the Samaritans also, an indiscriminate confusion swept through Palestine. Now all the residents of my own Caesarea2 and of all the other cities, regarding it as a foolish thing to undergo any suffering in defence of a senseless dogma, adopted the name of Christians in place of that which they then bore and by this pretence succeeded in shaking off the danger arising from the law. And all those of their number who were persons of any prudence and reasonableness showed no reluctance about adhering loyally to this faith, but the majority, feeling resentment that, not by their own free choice, but under compulsion of the law, they had changed from the beliefs of their fathers, instantly inclined to the Manichaeans and to the Polytheists, as they are called. And all the farmers, having gathered in great numbers, decided to rise in arms against the Emperor, putting forward as their Emperor a certain brigand, Julian by name, son of Savarus. And when they engaged with the soldiers, they held out for a time, but finally they were defeated in the battle and perished along with their leader. And it is said that one hundred thousand men perished in this struggle, and the land, which is the finest in the world, became in consequence destitute of farmers. And for the owners of the land who were Christians this led to very serious consequences. For it was incumbent upon them, as a matter of compulsion, to pay to the Emperor everlastingly, even though they were deriving no income from the land, the huge annual tax, since no mercy was shown in the administration of this business.

He then carried the persecution to the “Greeks,” as they are called, torturing their bodies and looting their properties. But even those among them who had decided to espouse in word the name of Christians, seeking thus to avert their present misfortunes, these not much later were generally seized at their libations and sacrifices and other unholy acts.3

1The polytheistic religions of Greece and Rome, the adherents of which were simply called “Hellenes”, i.e. Greeks; and various Christian and Jewish sects.

2Caesarea in Palestine was the birthplace of Procopius

3Procopius: The Secret History, trans. based on H.B. Dewing, Loeb Classical Library, 1935, pp. 137-141

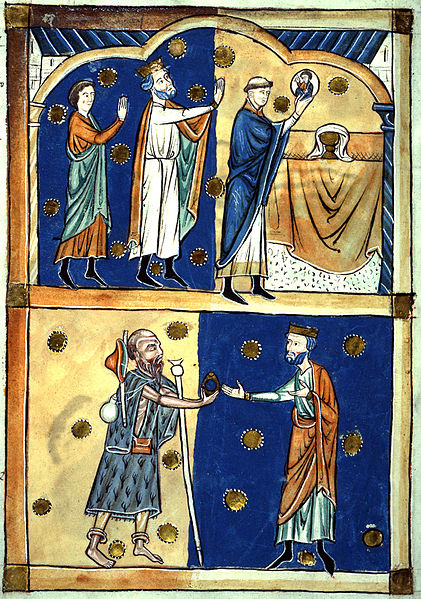

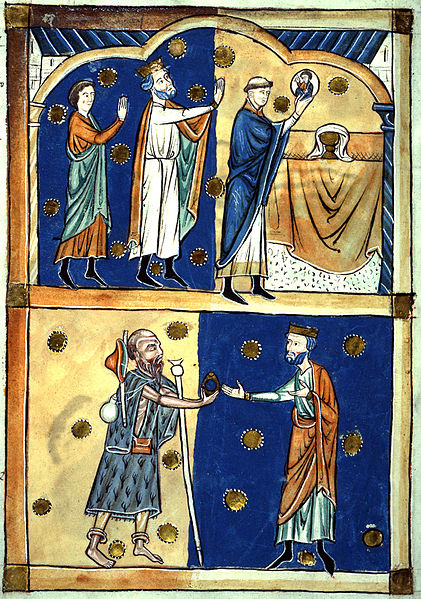

Page from a 13th century Abbreviatio (abridgement) of Domesday Book. Above King Edward the Confessor and Earl Leofric of Mercia see the face of Christ appear in the Eucharist wafer and below the return of a ring given to a beggar who was John the Baptist in disguise.

Still in the 6th century, and still with Gregory of Tours. He describes several miracles. Most have to do with recovering from illnesses. Generally speaking, when they got very ill, people expected they were going to die. And seeing as they didn’t understand how diseases worked and doctors, by this time in the West, were tending towards extinction, practically every recovery was considered miraculous. There are some other kinds of miracles too, several that are particularly amusing, and all of the variety to which we, with our 21st century minds, would say: “Hmm… Yeeess… Of course that’s what happened.”

Observance of the Lord’s Day

Book in Honour of the Martyrs: Chap. 15

In the territory of this city [Tours] at Lingeais, a woman who lived there moistened flour on the Lord’s day and shaped a loaf, and drawing the coals aside she covered it over with hot ashes to bake. When she did this her right hand was miraculously set on fire and began to burn. She screamed and wept and hastened to the village church in which relics of the blessed John are kept. And she prayed and made a vow that on this day sacred to the divine name she would do no work, but only pray. The next night she made a candle as tall as herself. Then she spent the whole night in prayer, holding the candle in her hand all the time and the flame went out and she returned home safe and sound.

Comparative “Merit” of Gregory and his Mother

Book in Honour of the Martyrs: Chap 85

. . . On this matter I recall what I heard told in my youth. It was the day of the suffering of the great martyr Polycarp, and his festival was being observed at Riom, a village of Auvergne. The reading of the martyrdom had been finished and the other readings which the priestly canon requires, and the time came for offering the sacrifice. The deacon, having received the tower1 in which the mystery of the Lord’s body was contained, started with it to the door, and when he entered the church to place it on the altar it slipped from his hand and floated along in the air and thus came to the altar, and the deacon was never able to lay hands on it; and I believe this happened for no other reason than that he was defiled in his conscience. For it was often told that he had committed adultery. It was granted only to one priest and three women, of whom my mother was one, to see this; the rest did not see it. I was present, I confess, at this festival at the time, but I had not the merit to see this miracle.

Miracles in Gregory’s Family

Miracles of St. Julian: Chap 23, 24

It happened once when he was trudging along on this journey, that he took his shoes off on account of the heat, and as he walked in his bare feet he stepped on a sharp thorn. This by chance had been cut, but was still lying on the ground and was concealed point upward in the green grass. It entered his foot and went clear through and then broke off and could not be drawn out. The blood ran in streams and as he could not walk he begged the blessed martyr’s aid and after the pain had grown a little less he went on his way limping. But the third night the wound began to gather and there was great pain. Then he turned to the source from which he had already obtained help and threw himself down before the glorious tomb; when the watch was finished he returned to bed and was overcome by sleep while awaiting the miraculous help of the martyr. On arising later he felt no pain and examining his foot he could not see the thorn which had entered it; and he perceived it had been drawn from his foot. He looked carefully for it and found it in his bed and saw with wonder how it had come out. When bishop he used to exhibit the place, where a great hollow was still to be seen, and to testify that this had been a miracle of the blessed martyr.

Miracles Worked on Gregory

The Four Books of the Miracles of St. Martin: Book 2; Chap 1

In the second month after my ordination, when I was at a country place, I suffered from dysentery and high fever and began to be so ill that I altogether despaired of living. Everything that I could eat was always vomited before it had been digested and I loathed food, and when my stomach had no more strength as a result of no food the fever was the only thing that gave me strength; I could in no way take anything substantial and strengthening. I had severe pain, too, that darted all through my stomach and went down into my bowels, exhausting me by its pain no less than the fever had done. And when I was in such a condition that no hope of life was left and everything was being made ready for my death and the physician’s medicine could do nothing for one whom death had laid claim to, I was in despair and called the chief physician Armentarius and said to him: “You have used every trick your profession, you have tried the power of all your remedies, but secular means are of no avail to the perishing. There is only one thing left for me to do. I will show you a great remedy: Let them bring dust from the holy master’s tomb and make a potion for me from it. And if this does not cure me, every means of escape is lost.” Then the deacon was sent to the tomb of the holy bishop just mentioned and he brought the sacred dust and put it in water and gave me a drink of it. When I had drunk soon all pain was gone and I received health from the tomb. And the benefit was so immediate that although this happened in the third hour, I became quite well and went to dinner that very day at the sixth hour.2

The Four Books of the Miracles of St. Martin: Book 3; Chap 1

I shall place first in this book a miracle that I experienced recently. We were sitting at dinner after a fast and eating, when a fish was served. The sign of the cross of the Lord was made over it, but as we ate, a bone from this very fish stuck in my throat most painfully. It caused me great distress, for the point was fastened in my throat and its length blocked the passage. It prevented my speaking and kept the saliva which comes frequently from the palate, from passing. On the third day, when I could get rid of it neither by coughing or hawking, I resorted to my usual resource. I went to the tomb and prostrated myself on the pavement and wept abundantly and groaned and begged the confessor’s aid. Then I rose and touched the full length of my throat and all my head with the curtain. I was immediately cured and before leaving the holy threshold I was rid of all uneasiness. What became of the unlucky bone I do not know. I did not cough it up nor feel it go down into my stomach. One thing only I know, that I so quickly perceived that I was cured that I thought that some one had put in his hand and pulled out the bone that hurt my throat.

The Four Books of the Miracles of St. Martin: Book 4; Chap 2

At one time my tongue became uncomfortably swelled up, so that when I wished to speak it usually made me stutter, which was somewhat unseemly. I went to the saint’s tomb and drew my awkward tongue along the wooden lattice. The swelling went own at once and I became well. It was a serious swelling and filled the cavity where the palate is. Then three days later my lip began to have a painful beating in it. I went again to the tomb to get help and when I had touched my lip to the hanging curtain the pulsation stopped at once. And I suppose this came from a over abundance of blood; still trusting to the saint’s power I did not try to lessen the [amount of] blood and this matter caused me no further trouble.

A Phantom Attacks a Woman

The Four Books of the Miracles of St. Martin: Book 3; Chap 37

At this time when a certain woman remained alone at the loom when the others had gone, a most frightful phantom appeared as she sat, and laid hold of the woman and began to drag her off. She screamed and wept since she saw there was no one to help, but still tried to make a courageous resistance. After two or three hours the other women returned and found her lying on the ground half dead and unable to speak. Still she made signs with her hand, but they did not understand and she continued speechless. The phantom which had appeared to her attacked so many persons in that house that they left it and went elsewhere. In two or three months’ time the woman came to the church and had the merit to recover her speech. And so she told with her own lips what she endured.

[And probably the best of the lot:]

A Fly Might Be A Demon

Book in Honour of the Martyrs: Chap 103

Pannichius, a priest of Poitou, when sitting at dinner with some friends he had invited, asked for a drink. When it was served a very troublesome fly kept flying about the cup and trying to soil it. The priest waved it off with his hand a number of times but it would go off a little and then try to get back, and he perceived that it was a crafty device of the enemy.3 He changed the cup to his left hand and made a cross with his right; then he divided the liquor in the cup into four parts and lifted it up high and poured it on the ground. For it was very plain that it was a device of the enemy.4

[  Eh??]

Eh??]

1 A vessel shaped like a tower which contained the host.

(Saint) Gregory of Tours

Let’s move on to the 6th century C.E. and the very famous (Saint) Gregory of Tours (November 30, c. 538 – November 17, 594), to whom we are truly indebted for writing The History of the Franks, the major historical source for the period. The Roman Empire in the West is no more, and we are now officially in the Middle Ages; that period of the Middle Ages formerly know as the Dark Ages. For various reasons most historians no longer like that term. I’m not sure I agree with them.

Book in Honour of the Martyrs: Preface

THE priest Jerome, next to the apostle Paul the best teacher of the church, tells us that he was brought before the judgmentseat of the eternal Judge and subjected to torture and severely punished because he was in the habit of reading Cicero’s clevernesses and Vergil’s lies, and that he said in the presence of the holy angels and the very Ruler of all that he would never thereafter read these, but would occupy himself in future only with such [writings] as would be judged worthy of God and suited to the edification of the Church. Moreover the apostle Paul says: “Let us follow after things which make for peace and things whereby we may edify me another.” And elsewhere: “Let no corrupt speech proceed out f your mouth; but such as is good for edifying, that it may give race to them that hear.” Therefore we too ought to follow after, to write, and to speak the things that edify the church of God, and with holy instruction bring weak minds to a knowledge of the perfect faith. And we ought not to relate lying tales nor to pursue the wisdom of philosophers that is hateful to God, lest by God’s judgment we fall under sentence of eternal death.

Gregory of Tours, History of the Franks, trans. Ernest Brehaut (extended selections), Records of Civilization 2, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1916)

Part 3, following on from part 1 and part 2.

Chapter XV.—Of Hypatia the Female Philosopher.

Chapter XV.—Of Hypatia the Female Philosopher.

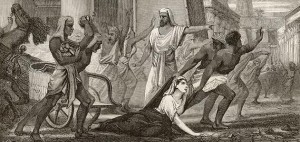

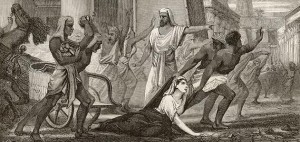

There was a woman at Alexandria named Hypatia, daughter of the philosopher1 Theon, who made such attainments in literature and science, as to far surpass all the philosophers of her own time. Having succeeded to the school of Plato and Plotinus, she explained the principles of philosophy to her auditors, many of whom came from a distance to receive her instructions. On account of the self-possession and ease of manner, which she had acquired in consequence of the cultivation of her mind, she not unfrequently appeared in public in presence of the magistrates. Neither did she feel abashed in coming to an assembly of men. For all men on account of her extraordinary dignity and virtue admired her the more. Yet even she fell a victim to the political jealousy which at that time prevailed. For as she had frequent interviews with Orestes, it was calumniously reported among the Christian populace, that it was she who prevented Orestes from being reconciled to the bishop. Some of them therefore, hurried away by a fierce and bigoted zeal, whose ringleader was a reader named Peter, waylaid her returning home, and dragging her from her carriage, they took her to the church called Cæsareum, where they completely stripped her, and then murdered her with tiles2.After tearing her body in pieces, they took her mangled limbs to a place called Cinaron, and there burnt them. This affair brought not the least opprobrium, not only upon Cyril,but also upon the whole Alexandrian church. And surely nothing can be farther from the spirit of Christianity than the allowance of massacres, fights, and transactions of that sort. This happened in the month of March during Lent, in the fourth year of Cyril’s episcopate, under the tenth consulate of Honorius, and the sixth of Theodosius.3

1 and mathematician. He arranged Euclid’s Elements and Ptolemy’s Handy Tables.

2 Tile shards, presumably, i.e. flayed her alive with something like this.

3 Socrates and Sozomenus, Ecclesiastical Histories, ed. and trans. Philip Schaff, WM. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Michigan, p. 160

Bishop Cyril of Alexandria

This is the first of three posts all of which deal with one series of events. The series of events leading to the murder of the pagan philosopher and scientist Hypatia by a Christian mob in Alexandria in 425 C.E. She was, however, but collateral damage in a much more important struggle; that of secular versus religious authority. Nevertheless, her death sealed the victory of religious authority, since after this the Prefect, Orestes, gives up his struggle against Bishop Cyril, he gradually fades from political life, and finally disappears from historical record altogether. Where he went, what he did in later life, where, when and how he died, we don’t know.

The text is from the Christian historiographer Socrates Scholasticus’s Historia Ecclesiastica. He was born in Constantinople c. 380 C.E. and died some time after 439. The full text of Historia Ecclesiastica in English translation can be found here.

Chapter XIII.—Conflict between the Christians and Jews at Alexandria: and breach between the Bishop Cyril and the Prefect Orestes.

About this same time it happened that the Jewish inhabitants were driven out of Alexandria by Cyril the bishop on the following account. The Alexandrian public is more delighted with tumult than any other people: and if at any time it should find a pretext, breaks forth into the most intolerable excesses; for it never ceases from its turbulence without bloodshed. It happened on the present occasion that a disturbance arose among the populace, not from a cause of any serious importance, but out of an evil that has become very popular in almost all cities, viz. a fondness for dancing exhibitions.

In consequence of the Jews being disengaged from business on the Sabbath, and spending their time, not in hearing the Law, but in theatrical amusements, dancers usually collect great crowds on that day, and disorder is almost invariably produced. And although this was in some degree controlled by the governor of Alexandria, nevertheless the Jews continued opposing these measures. And although they are always hostile toward the Christians they were roused to still greater opposition against them on account of the dancers. When therefore Orestes the prefect was publishing an edict—for so they are accustomed to call public notices—in the theatre for the regulation of the shows, some of the bishop Cyril’s party were present to learn the nature of the orders about to be issued. There was among them a certain Hierax, a teacher of the rudimental branches of literature, and one who was a very enthusiastic listener of the bishop Cyril’s sermons, and made himself conspicuous by his forwardness in applauding.

When the Jews observed this person in the theatre, they immediately cried out that he had come there for no other purpose than to excite sedition among the people. Now Orestes had long regarded with jealousy the growing power of the bishops, because they encroached on the jurisdiction of the authorities appointed by the emperor, especially as Cyril wished to set spies over his proceedings; he therefore ordered Hierax to be seized, and publicly subjected him to the torture in the theatre.

Cyril, on being informed of this, sent for the principal Jews, and threatened them with the utmost severities unless they desisted from their molestation of the Christians. The Jewish populace on hearing these menaces, instead of suppressing their violence, only became more furious, and were led to form conspiracies for the destruction of the Christians; one of these was of so desperate a character as to cause their entire expulsion from Alexandria; this I shall now describe. Having agreed that each one of them should wear a ring on his finger made of the bark of a palm branch, for the sake of mutual recognition, they determined to make a nightly attack on the Christians.

They therefore sent persons into the streets to raise an outcry that the church named after Alexander was on fire. Thus many Christians on hearing this ran out, some from one direction and some from another, in great anxiety to save their church. The Jews immediately fell upon and slew them; readily distinguishing each other by their rings.

At daybreak the authors of this atrocity could not be concealed: and Cyril, accompanied by an immense crowd of people, going to their synagogues—for so they call their house of prayer—took them away from them, and drove the Jews out of the city, permitting the multitude to plunder their goods. Thus the Jews who had inhabited the city from the time of Alexander the Macedonian were expelled from it, stripped of all they possessed, and dispersed some in one direction and some in another. One of them, a physician named Adamantius, fled to Atticus bishop of Constantinople, and professing Christianity, some time afterwards returned to Alexandria and fixed his residence there.

But Orestes the governor of Alexandria was filled with great indignation at these transactions, and was excessively grieved that a city of such magnitude should have been suddenly bereft of so large a portion of its population; he therefore at once communicated the whole affair to the emperor. Cyril also wrote to him, describing the outrageous conduct of the Jews; and in the meanwhile sent persons to Orestes who should mediate concerning a reconciliation: for this the people had urged him to do. And when Orestes refused to listen to friendly advances, Cyril extended toward him the book of gospels,believing that respect for religion would induce him to lay aside his resentment. When, however, even this had no pacific effect on the prefect, but he persisted in implacable hostility against the bishop, the following event afterwards occurred.1

1Socrates and Sozomenus, Ecclesiastical Histories, ed. and trans. Philip Schaff, WM. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Michigan, p. 159-160

Let us stay in the 6th century for a bit, but this time move to the East. Justinian I (c. 482 C.E. – 14 November 565 C.E.), known as The Great – which I deliberately place in inverted commas – was Byzantine Emperor from 527-565 C.E. He is considered a saint by the Easter Orthodox Church. He famously married his mistress Theodora, a professional courtesan, who became extraordinarily influential in the politics of the Empire. Justinian sought to revive the Empire’s greatness by reconquering the lost western half of the Roman Empire. He oversaw the uniform rewriting of Roman Law, the Corpus Juris Civilis, which is still the basis of civil law in many modern states. Unfortunately he also wrote many laws, and changed earlier ones; for example forbidding women from getting divorced except under very specific circumstances, whereas previously, because marriage relied on the concept of consent, women could divorce by simply not wishing to be married any more. All they needed do was send a note to their husbands informing them of the fact. Without consent, there was no marriage under earlier Roman Law. Now, a woman could divorce her husband only if one of the following reasons applied:

Let us stay in the 6th century for a bit, but this time move to the East. Justinian I (c. 482 C.E. – 14 November 565 C.E.), known as The Great – which I deliberately place in inverted commas – was Byzantine Emperor from 527-565 C.E. He is considered a saint by the Easter Orthodox Church. He famously married his mistress Theodora, a professional courtesan, who became extraordinarily influential in the politics of the Empire. Justinian sought to revive the Empire’s greatness by reconquering the lost western half of the Roman Empire. He oversaw the uniform rewriting of Roman Law, the Corpus Juris Civilis, which is still the basis of civil law in many modern states. Unfortunately he also wrote many laws, and changed earlier ones; for example forbidding women from getting divorced except under very specific circumstances, whereas previously, because marriage relied on the concept of consent, women could divorce by simply not wishing to be married any more. All they needed do was send a note to their husbands informing them of the fact. Without consent, there was no marriage under earlier Roman Law. Now, a woman could divorce her husband only if one of the following reasons applied: